The 80% Rule: Who Captures Value When AI Does the Work

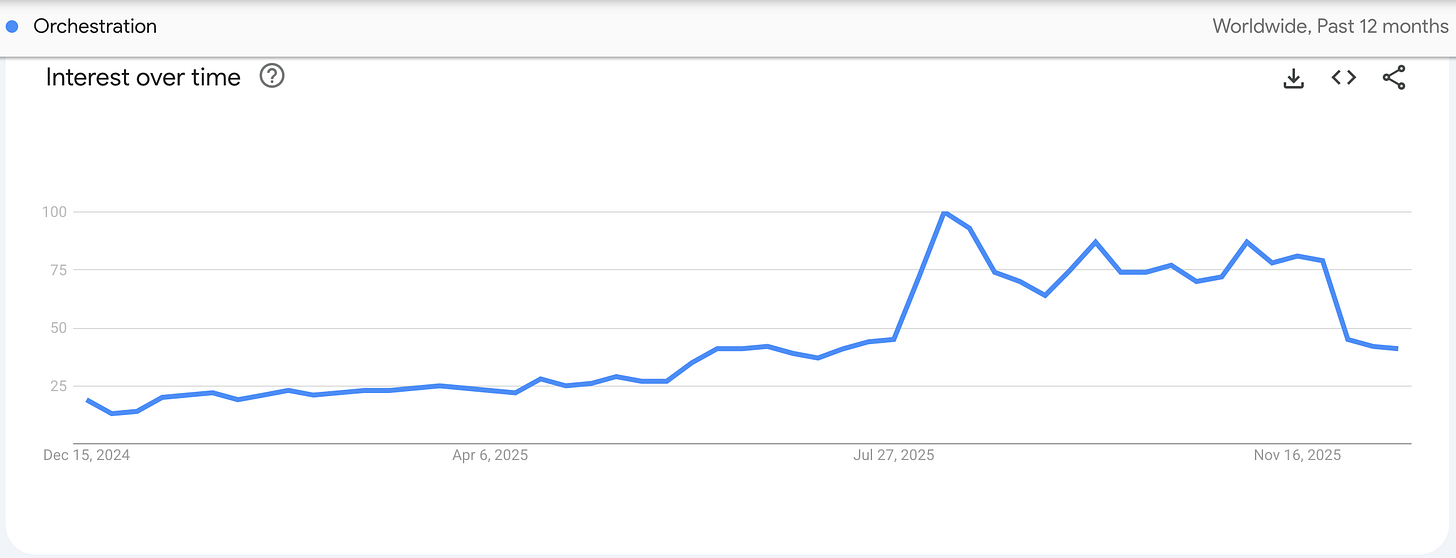

Google Research just showed that centralized orchestration of agentic systems drives 80% higher AI performance. Translated into dollars, we get a first glimpse of Orchestration Economics.

Google Research just demonstrated that centralized orchestration delivers ~80% higher agent performance than single-agent systems in certain configurations. That’s the difference between AI as an assistant and AI as an agentic colleague. That 80% accrues to whoever controls the orchestrator - the “captain” - not to the specialist agents being coordinated - the “crew.” Having great agents does not mean you capture value. Owning the control plane where your agentic colleagues receive intent and direct work does. I call this strategic position Orchestration.

This is not a story about technology companies. This is a story about every company.

The insurance underwriter evaluating flood risk. The bank’s credit committee pricing commercial loans. The procurement team at a manufacturing company negotiating supplier contracts. The hospital system coordinating patient care across specialists. The freight brokerage company optimizing transportation costs.

They are all about to face the same question: When AI agents can do the thinking for an expanding range of tasks, who decides which agents get called?

Or, to put the questions in agentic AI terms: Who controls the orchestration?

That question will determine which companies capture value in the next decade and which companies become cost centers in someone else’s value chain.

Google Research and DeepMind just published a study that provides a startling glimpse into the new era of “Orchestration Economics.” This period has the potential to see one of the greatest value migrations in history as swarms of autonomous agentic AI systems allow technology to move beyond competing for IT budgets to capturing trillions of dollars in global labor costs. These systems will give rise to entirely new categories of companies, which will force both incumbent tech and non-tech companies to re-evaluate their business models and moats.

We are only just on the cusp of this transformation, but the latest Google research should nevertheless provide a jolt to anyone still not paying attention. I’ll dive into the results in more detail below, but here’s the key finding:

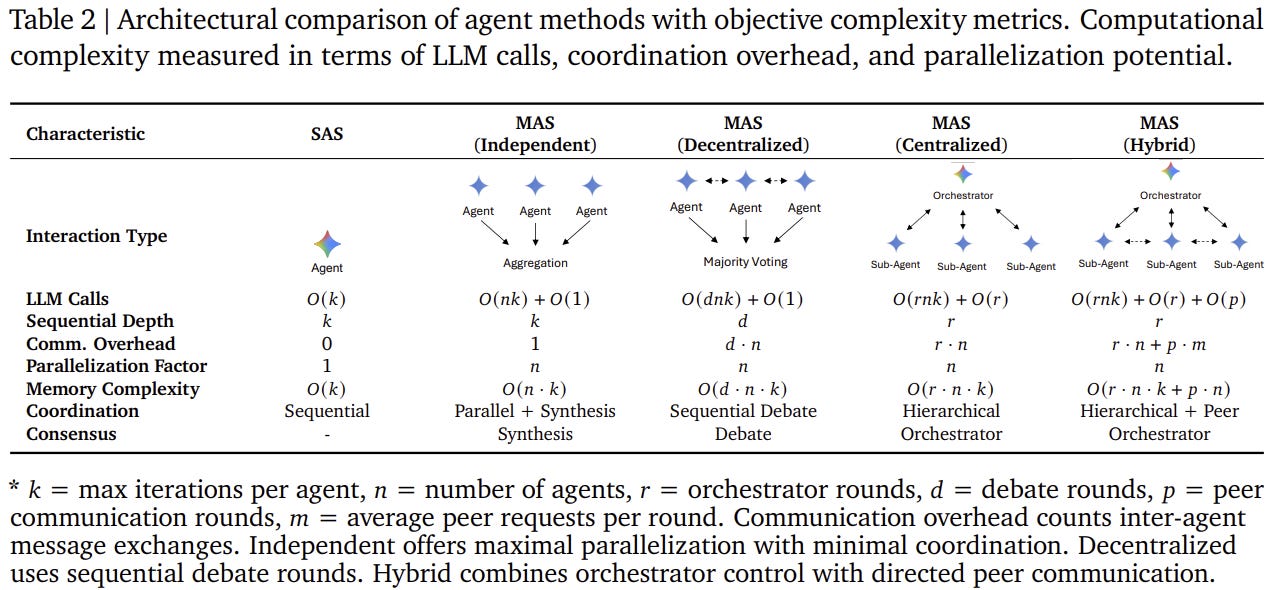

On the structured tasks that dominate enterprise work, centralized orchestration (“MAS (Centralized)” per figure below) delivered 80.9% higher performance than single-agent systems.

In other words, it’s not enough to have the best agent. Or a single agent. The companies learning to master that orchestration layer are achieving the difference between a useful assistant and autonomous execution. Between software you buy and headcount you replace. Between linear productivity gains and exponential workflow transformation.

I first began talking about the importance of orchestration last March, which seems both recent and forever ago. That was just a few months after Anthropic released its Model Context Protocol (MCP) in November 2024, an “open standard that enables developers to build secure, two-way connections between their data sources and AI-powered tools.” At that point, Anthropic was still mostly referring to “AI Assistants” rather than “Agents.”

Last week, the Linux Foundation officially created the Agentic AI Foundation to oversee open-source agentic projects. As part of that, Anthropic donated MCP, which has effectively become the standard orchestration tool, to be governed going forward by the new foundation.

In between, the whole tech world has seized upon talk of agents and orchestration with a vengeance.

This is where we start to see the true generative and agentic AI discontinuity take hold. These technologies are pushing the world past classic disruption that accelerates existing curves into discontinuity that breaks the curves and creates a new one. Previous benchmarks, playbooks, and strategies are becoming obsolete, and we have entered a period of confusion and uncertainty.

Of course, when this happens, jargon and hype have a way of obscuring rather than clarifying. So, I want to step back here and use this latest study as an opportunity to do a couple of things.

First, let’s really make it clear what we’re talking about when we’re talking about orchestration. Again, with every hype cycle, companies know how to play the game of adding a slide with the right buzzword to their pitch deck or dropping the right lingo in their earnings call. Everyone says their products have orchestration features. Only some of them are telling the truth. You have to know how to tell the difference.

Second, you have to understand why you should care. Maybe it’s obvious. Possibly you’re a SaaS CEO, and you already lie awake at night staring at the ceiling because you know your moat is collapsing. But maybe you’re a Fortune 500 CEO of an analog company, and you think all of this is still science-fiction.

Defining Orchestration

Every company selling AI says they do orchestration. Palantir’s whole pitch is orchestration. UiPath called their product Maestro, C3.AI is the leading AI orchestration platform. And so on.

If you attend AI conferences, you will see the same slide a hundred times. There is always a box in the middle labeled “orchestration layer.”

But, to paraphrase, orchestration is in the eye of the beholder.

In this case, what that word signifies is very different depending on where the companies sits in the tech stack, their relationship to hardware to software, and (somewhat cynically) how they are trying to convince markets of their solution’s relevance in the Agentic Era. Here’s what it could mean:

Infrastructure orchestration. This is a routing role, a layer that wires APIs together, manages workflows, and handles the plumbing to coordinate across the broader system. It manages things such as allocating computational resources and helps ensure scaling and reliability. Think Palantir’s AIP connecting models to enterprise data.

This is sophisticated engineering. It solves hard problems. It has real value - Palantir’s $437B market cap reflects genuine capability. It remains, by far, the best valued software company (~76,5x EV/NTM revenue – ~156x EV/NTM FCF). Companies need infrastructure orchestration to run AI at enterprise scale.

But here is what infrastructure orchestration does not do: it does not decide what work to do. It does not receive user intent and translate it into a plan. It does not choose which agents to invoke for which subtasks. It does not validate outputs and determine when a goal is achieved.

Infrastructure orchestration asks: “How do we run these agents reliably?”

Agentic orchestration asks: “Which agents should we run, in what order, to accomplish this goal?”

The first is infrastructure. The second is command.

Agentic orchestration. This is a reasoning role. An agent sits where user intent enters the system - an insurance submission, a loan application, a procurement request, a customer service inquiry. It interprets that intent. It decides what to do, why, and in what sequence. It decomposes the goal into subtasks. It selects which specialist agents to invoke. It validates their outputs. It determines when the work is complete.

In the Google notation: the agentic orchestrator is a_orch, the agent that embodies the orchestration policy Ω. It is not middleware. It is not a workflow engine. It is a reasoning agent with a specific job: captain.

Back to Palantir. While the company offers powerful platforms, their customers remain in control of strategic decision-making. The company functions more like an advanced technological support system than an autonomous orchestrator. Their AI and data integration capabilities enhance existing workflows without replacing human-driven intent and direction. In some classified government contexts, Palantir may sit closer to the agentic orchestration position - analysts expressing intent directly into Foundry, with Palantir’s system coordinating the workflow. But in most commercial deployments, the customer owns the orchestration layer.

The strategic value difference between both is stark:

Infrastructure orchestration enables scale. Agentic orchestration captures value.

Infrastructure orchestration is called by the system. Agentic orchestration calls the system.

Infrastructure orchestration competes on reliability and cost. Agentic orchestration accumulates moats.

Both are necessary. One commands a superior premium.

Palantir’s $437B valuation implicitly prices in orchestration economics. But their current architecture - selling platforms that customers deploy within customer-controlled workflows - is infrastructure orchestration, not agentic orchestration. The moat is real. The premium may not be. Palantir could become an orchestrator if their AIP becomes the surface where users express intent and Palantir’s system decomposes that into agent workflows autonomously. But today, that is not yet the case.

Captain vs. Crew

Once you accept that every node in the chain can think, the next question is obvious: Who will seize that captain’s seat? Who will claim the orchestrator mantle?

Remember, in the agentic system defined by Google, agents share the same formal structure. They observe. They reason. They act. They update their histories. The agents have similar status in the agentic chain.

But in a centralized system, one agent has a different job.

It ingests the task specification, the closest thing to what the user actually wanted. Process this insurance claim. Evaluate this loan application. Optimize this supply chain.

It decides how to break that into subtasks and which agents will do them.

It collects their outputs. It checks them. It decides what happens next.

That is the orchestrator. It is not a router. It is not a rules engine. It is a reasoning agent assigned to one specific role: captain.

Below the captain sit the crew. Specialized agents whose job is to execute well-scoped work. They can be brilliant within their domains - pricing, risk modeling, code generation, research, whatever. But they do not see the whole map. They do not decide which workflow to run. They do not own the relationship with the human who asked for the outcome.

The human asked the captain. The captain told the crew. The crew did the work. The captain reported back.

This hierarchy emerges because complex goals are open-ended. Someone has to translate fuzzy intent into a specific plan. Someone has to decide which tools to invoke and in what order. Someone has to maintain coherence when things go wrong and agents disagree.

In human organizations, we call that management.

In multi-agent systems, we call it orchestration.

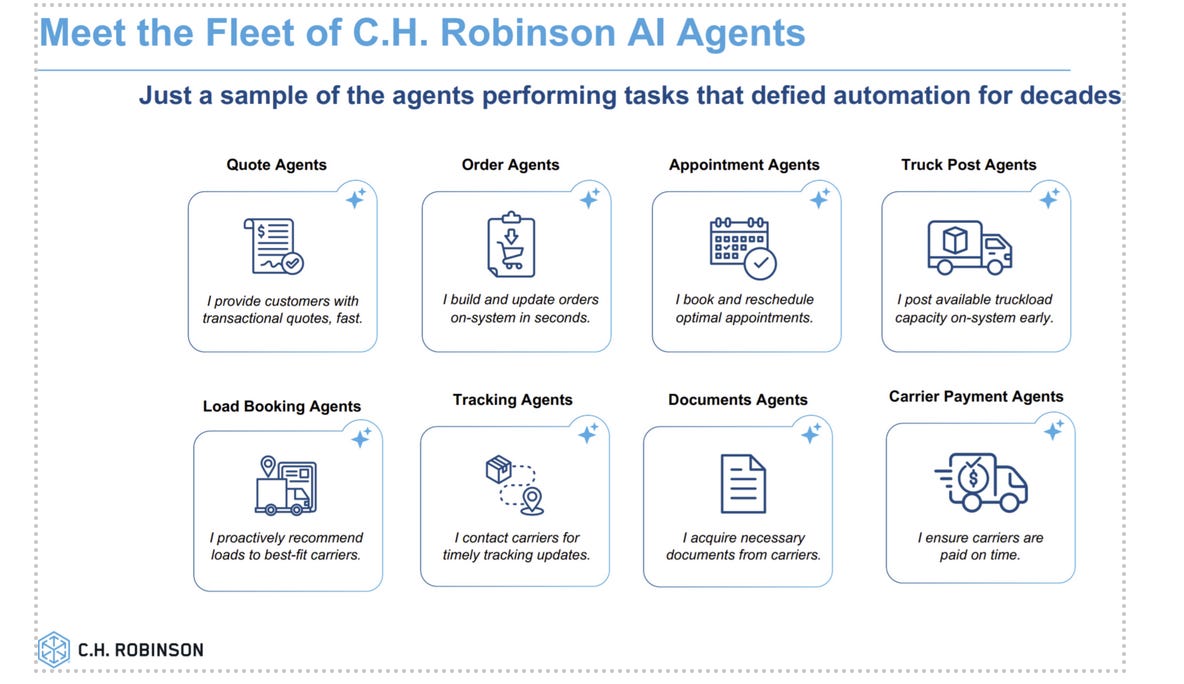

If an insurance company builds a claims processing agent that receives submissions and coordinates extraction agents, medical coding agents, fraud detection agents, and pricing agents, then that insurance company is the orchestrator for its own claims workflow. Everyone it calls is crew.

If OpenAI’s ChatGPT is the surface where users express goals and an internal orchestrator decides when to call which tools, then OpenAI is the orchestrator in that context. Even if it calls other companies’ models or APIs.

The label follows the architecture. Not the narrative.

Real-World Orchestration

Let’s see how this unfolds in the real-world.

A commercial insurance submission arrives. It enters a human chain and is received by an intake specialist. It then moves through an established organizational workflow: data gathering, risk engineering, Pricing, Approval, and then document generation.

Each specialist applies intelligence locally. They coordinate over email. They have meetings. They update shared spreadsheets. They argue about edge cases in the hallway.

The orchestration layer lives in a manager’s brain and a project management tool.

The bottleneck is the human capacity to coordinate. The economics, especially the costs, remained linked to some degree by the ability to scale that human labor, even with productivity gains more recently from digital tools.

This is how most complex work still runs. Chains of intelligent humans, connected by calendars and urgency. Those digital tools and platforms introduced disruption in some cases, which led to greater efficiencies, expanded capacity, and improved margins. But they did not fundamentally break this human chain.

Here is how I think work will happen as agentic orchestration expands. Or, is already happening, depending on which industry you’re in and which company you are at.

A submission arrives. Perhaps through Slack, or through an ERP. But it lands somewhere different now. It lands at a master agent.

The master agent does not “process a document.” That is what the old software did. The master agent interprets a goal: Evaluate this risk and produce a quote that fits our growth and risk constraints.

It inspects the case. It decides which specialized agents to invoke. This could be extraction, enrichment, risk modeling, pricing, or compliance validation. It sets their inputs. It asks them to work.

The specialists are agents, too. They have real reasoning capacity. They can read documents, run analyses, and generate recommendations. They are valuable.

But they are no longer where the workflow is decided. Their job is to respond to the plan. Not to define it.

This is the shift. The control plane moves.

In the old world, control sat in human management structures and process documentation.

In the agentic world, control sits in the orchestrator agent and its policy: Ω. These are the rules that encode how intent becomes action, how work gets decomposed, and when it is done.

This is where we start to see discontinuity. These agentic systems, with the right orchestration, promise not just to replace an existing piece of software. They hold the potential to automate entire functions of human labor.

Historically, more software or more headcount had proportional effects. Linear improvements for linear investment.

With agentic systems, the potential is for exponential gains.

If...they work as promised.

Which brings us back to the latest study.

Orchestration State of Play

The research comes at a time of massive progress on the model side, with last week’s GPT-5.2, Gemini 3, and Claude Opus 4.5 pushing intelligence indices higher while costs continue to drop. And of course, open-source models (notably Chinese) too. This means the underlying foundation of these systems continues to become smarter and less expensive, even as they add greater orchestration capacity.

For the study, the Google team tested agent systems across four benchmarks: financial reasoning, web navigation, game planning, and workflow execution. The kind of tasks that matter to companies trying to replace headcount with automation.

They ran 180 controlled experiments. They held everything constant: the models, the prompts, the tools, and the compute budgets. They only changed how agents coordinate with each other.

On the structured tasks that dominate enterprise work, from claims processing to financial analysis to supply chain optimization, centralized orchestration delivered 80.9% higher performance than single-agent systems.

On financial reasoning tasks such as “analyze this company’s fundamentals,“ centralized architectures with an orchestrator delivered around 80% higher success than single-agent systems under the same token budget.

Now compare that to architectures without centralized orchestration, where independent agents were doing their own thing and combined results at the end. In these cases, errors were amplified by 17.2x. Each agent’s mistakes flowed unchecked into the final synthesis. Garbage in, garbage out, garbage compounding exponentially.

Centralized systems with an orchestrator cut error amplification to 4.4x. That is a 75% reduction in error propagation. The orchestrator acted as a validation bottleneck. It intercepted sub-agent outputs. It caught mistakes before they could cascade. In our captain metaphor, the captain caught the crew’s errors before they sank the ship.

But –the study also comes with a very important caveat: the orchestration advantage was task-dependent.

On tightly sequential planning tasks where everything has to happen in order, any multi-agent scheme under a fixed budget actually hurts performance.

On structured, parallelizable tasks, such as the kind that dominate enterprise workflows from insurance underwriting to credit analysis to supply chain planning, centralized orchestration improves performance and creates value. Changing the coordination topology by introducing an orchestrator and giving it authority creates a step-change in performance for certain task classes.

The 80% does not get distributed evenly across the graph. It accrues where the architecture says the leverage is: at the orchestrator, where plans are made, agents are selected, and errors are caught.

This is an important takeaway that echoes a similar finding from a recent Carnegie Mellon and Stanford University study that showed AI agents complete some realistic workflows 88.3% faster at 90.4-96.2% lower cost than humans. That was true, but only for a certain set of very narrowly defined tasks.

The key, in both cases, is understanding the broader concepts as well as where the technology is today, and how that maps to your organization to identify where to find those gains. Over time, the technology will mature, and the use cases will expand. But both studies offered similar warnings: push too far, too soon, in the wrong place, and you’ll find yourself going backward.

Orchestration Economics: From Assistant to Autonomous

So, why does 80% matter economically?

Enterprise workflows have a pass/fail bar. Below about 70% reliability, they require human supervision. Every case is reviewed. AI is a helpful assistant. Humans still do the work.

Above about 85% reliability, workflows can run autonomously with exception handling. AI does the work. The human handles outliers.

The difference between 70% and 85% is not just a 15% productivity improvement. It is a category change.

An insurance company that can auto-process 85% of submissions is not using software to help underwriters work faster. It is replacing underwriters with software and hiring exception handlers to handle the 15%.

The 80% performance delta from centralized orchestration is frequently the difference between those two states.

Consider a commercial bank doing credit analysis:

Single-agent system: 45% task completion → every deal requires analyst review → marginal productivity gain → you bought software, charged it to the IT budget, called it innovation

Centralized orchestration: 81% task completion → autonomous processing with exception escalation → headcount substitution → you replaced salary expense with compute expense.

This is the difference between a business model based on selling software licenses priced per seat, $50-200/month, and fighting for IT budget, and a business model priced per outcome or per task that is trying to replace some or all labor budgets.

That restructuring is a one-time event per company. The vendor who enables this agentic systems orchestration owns the relationship. Once intelligence is abundant, the old rules about value capture stop working.

The new scarcity is coordination authority. Who controls Ω? Who operates a_orch? Who receives the user’s intent and translates it into a plan?

The Compounding Moats: Why First Wins

If you are the CEO of Palantir (or any other company, for that matter), why does the difference between Agentic and Infrastructure Orchestration matter? The answer goes beyond just the ability to upsell or any traditional moves from the SaaS playbook.

The orchestrator accumulates three reinforcing advantages that specialists will find hard to replicate:

Every interaction teaches the orchestrator’s policy Ω how to decompose tasks better. Which agents work well together. Which error patterns to watch for. Which shortcuts save tokens without sacrificing accuracy.

This learning compounds within the orchestrator. A pricing agent that gets called by fifty orchestrators does not learn from that cross-pollination. Each orchestrator-agent interaction is stateless from the pricing agent’s perspective.

But the orchestrator sees patterns across thousands of cases, dozens of agent combinations, accumulating tacit knowledge about coordination itself. Pattern libraries become the moat in the Agentic Era.

For a health insurer, this might mean learning that certain claim types need medical records enrichment before pricing, while others can go straight to adjudication. Small optimization. Multiplied across millions of claims annually, that translates into a massive efficiency gain.

2. Integration Lock-In

Once workflows embed orchestrator-specific decomposition patterns, migration requires rebuilding coordination logic.

It is one thing to swap out a single-agent pricing API. You change an endpoint. You test it. You ship it.

It is another thing to migrate orchestration logic when your entire claims processing workflow has evolved around how one orchestrator decomposes intent, validates outputs, and handles exceptions.

You are not changing an API. You are rewriting how your business operates and significantly improving your “Quality of Revenue” with higher retention rates.

3. Cross-Side Network Effects

As more specialist agents integrate with an orchestrator, the platform’s capability surface expands. An insurance orchestrator that can call 50 specialist agents is more valuable than one that calls 10.

As more users express intent through an orchestrator, the volume of decomposition tasks increases, justifying specialist development. More specialists appear. Capability expands. More users arrive. Here you are increasing your “Quality of Growth”, as orchestration powers expansion dynamics across the customer base.

The 80% performance delta creates the initial adoption wedge. Once users cross the autonomous execution threshold, these compounding dynamics lock them in.

By the time competitors recognize the game, the leading orchestrator has accumulated context, integration depth, and network scale that cannot be replicated by starting from zero.

The Discontinuity Thesis

The Google paper quantifies a discontinuity: changing coordination topology - while holding models, tools, and compute constant - creates step-function performance gains on enterprise-relevant task classes.

The agentic stack has clear stratification: compute (Nvidia/hyperscalers), models (OpenAI/Anthropic/Google), orchestration, and specialist agents. The 80% delta suggests orchestration is where platform economics emerge. The layer that controls how user intent becomes multi-agent plans - that owns Ω and operates a_orch - captures coordination rent and accumulates moats that specialist agents cannot replicate.

But unlike previous technology cycles, this layer is not reserved for technology companies. Orchestration is defined by owning the control plane where intent enters and plans are made. That control plane can live anywhere.

Salesforce can be the orchestrator for CRM workflows. But so can Disney, now a new OpenAI partner, for guest experience. Caterpillar for equipment operations. JP Morgan for banking. For the first time, the strategic layer of the stack is contestable by companies that own domain expertise, customer relationships, and operational context - not just the companies that write software.

The 80% performance delta is the economic catalyst that separates orchestrators from crew. It is where the new Durable Growth Moats will be built.

The companies that will capture asymmetric returns are those building genuine orchestrator positions: receiving user intent, controlling task decomposition, validating specialist outputs, and accumulating the context that makes Ω increasingly defensible.

This is the birth of Orchestration Economics™.