OpenAI and xAI: When Megawatts Become the New ARPU

OpenAI’s CFO handed the AI industry its first industrial metric in advance of an anticipated IPO. Ironically, if it holds, the equation favors xAI and Elon Musk. But likely, it will fall apart.

OpenAI’s “Megawatt-to-Revenue” metric (MRE) claims $1GW of compute linearly generates $10M in revenue, framing AI as an industrial commodity. If this holds, xAI’s grid-independent $1GW+$ clusters position Elon Musk to capture the value OpenAI’s own equation implies. However, “Compute Payback” is the truer lens, measuring how fast gross profits recoup training costs.

At the World Economic Forum in Davos last week, OpenAI Chief Financial Officer Sarah Friar made the surprising suggestion that the “intelligence race” resembled a kind of industrial economics.

In her January 18 blog post and subsequent appearances on CNBC, Friar framed OpenAI’s growth as a near-linear correlation between compute power and revenue growth:

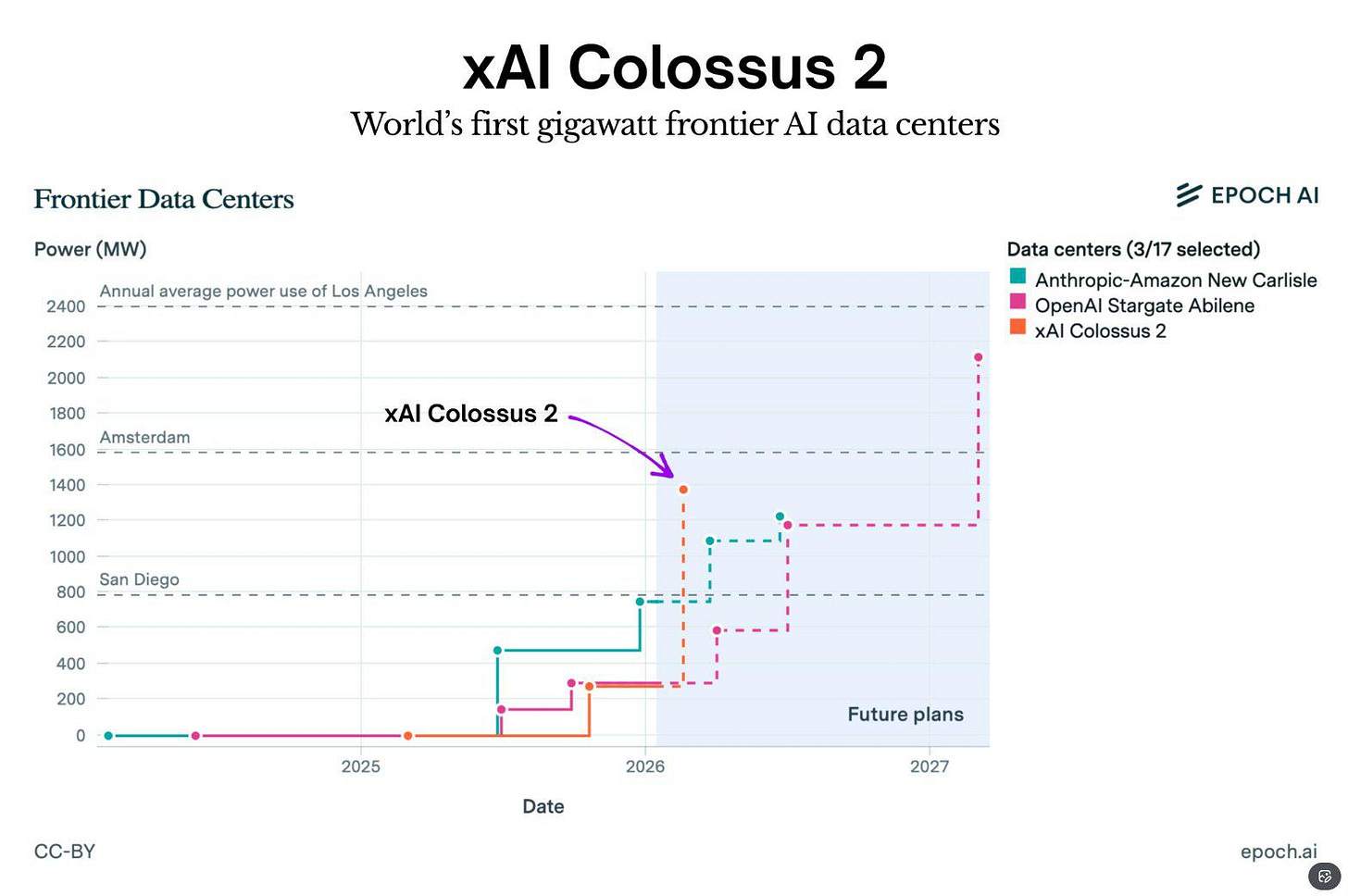

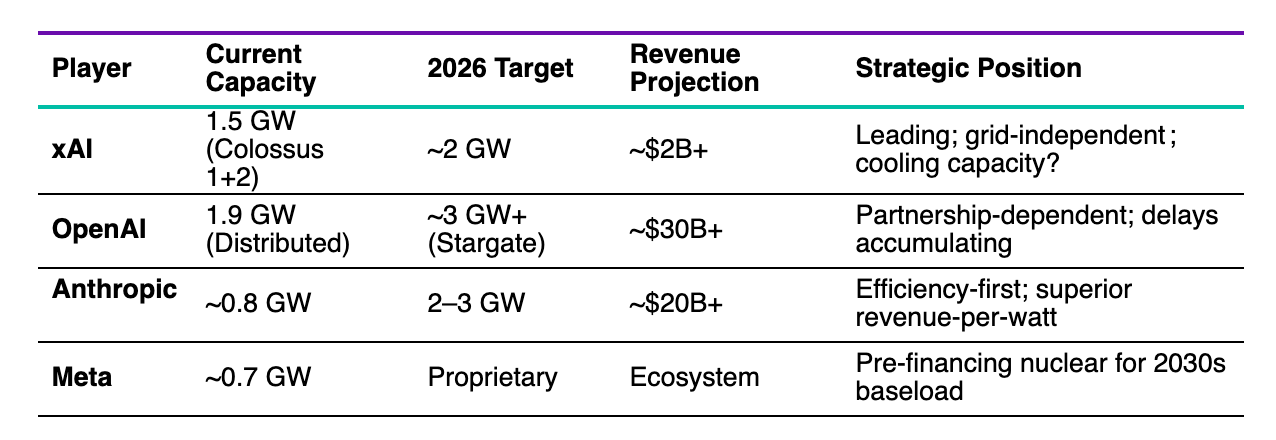

“Looking back on the past three years, our ability to serve customers—as measured by revenue—directly tracks available compute: Compute grew 3X year over year or 9.5X from 2023 to 2025: 0.2 GW in 2023, 0.6 GW in 2024, and ~1.9 GW in 2025. While revenue followed the same curve, growing 3X year over year, or 10X from 2023 to 2025: $2B ARR in 2023, $6B in 2024, and $20B+ in 2025. This is never-before-seen growth at such scale. And we firmly believe that more compute in these periods would have led to faster customer adoption and monetization.”

She positioned this as a critical competitive advantage for OpenAI:

“Compute is the scarcest resource in AI. Three years ago, we relied on a single compute provider. Today, we are working with providers across a diversified ecosystem. That shift gives us resilience and, critically, compute certainty. We can plan, finance, and deploy capacity with confidence in a market where access to compute defines who can scale.”

If this dynamic were to become the fundamental guiding economic principle of AI, it would be a dream for investors. The AI industry would finally have acquired its equivalent of “barrels per day” in petroleum or Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) in telecommunications. One gigawatt yields roughly $10 billion in annual recurring revenue. Wall Street would have a new acronym to track every quarter: Megawatt-to-Revenue Equation (MRE).

Simple. Investable. Seductive.

Unfortunately, from the point of view of OpenAI and the industry more broadly, drawing such a linear connection between compute and revenues contains two major flaws: one physical, one algorithmic.

First, if one could really make such an extrapolation, then the true king right now might be xAI, which just announced that Colossus 2 had become operational at 1 GW capacity, rendering it the first gigawatt-scale AI training cluster in history. And yet, not too many observers believe xAI is winning either the consumer or enterprise race in terms of revenue, at least not yet. But no matter which players claim infrastructure superiority, the reality of physical world constraints, such as politics and energy, stand ready to crush this equation.

Second, and perhaps more problematic, is that this compute-revenue flywheel presupposes that algorithmic innovation remains subordinate to raw scaling. That more power invariably yields proportionally more intelligence. That the future resembles the past, merely enlarged. And yet, as I have written several times in recent months, this assumption, which has been the underpinning of the explosive Capex spending by Big Tech, faces a growing array of technical and geopolitical challenges that could turn apparent infrastructure moats into costly stranded assets.

As we plunge into 2026, a year that could feature IPOs for such LLM headliners as OpenAI and Anthropic, it is essential that investors – and executives alike - grasp how the ongoing generative and agentic AI discontinuity is reshaping the economic paradigm around fundamental aspects such as infrastructure.

The Novelty of Compute as Currency

Until now, AI infrastructure narratives have fixated on GPU counts, floating-point operations, or parameter scales. These metrics conveyed little to generalist investors parsing quarterly reports in search of the signs that would unlock the hidden meaning buried in the data.

Megawatts, by contrast, possess industrial legibility. They appear on utility bills. They require permits. They are, in the most literal sense, grounded in physical reality. It is a metric that feels tangible.

This reframing serves an unmistakable strategic purpose.

OpenAI is reportedly preparing for a public offering while carrying an estimated $14 billion in 2026 operating losses and staggering infrastructure commitments: $250 billion in Azure capacity agreements, $38 billion with AWS, and upwards of $1 trillion in chip pre-orders through the decade.

Friar’s equation furnishes the narrative scaffolding to justify this capital intensity. If revenue scales linearly with power, then every dollar committed to data centers represents future ARR waiting to be unlocked.

Friar describes compute as part of OpenAI's compounding system. Investment in compute powers frontier research. Superior models yield superior intelligence that can lead to more powerful models, but also more efficient inference for daily usage. Adoption drives revenue. Revenue funds the next wave of compute. The cycle creates a perpetual growth loop, each rotation reinforcing the last. (Critics have a less charitable view of the financial view the various financial entanglements between OpenAI and its customers-slash-partners-slash-investors-slash-suppliers.)

“Infrastructure expands what we can deliver,” she wrote. “Innovation expands what intelligence can do. Adoption expands who can use it. Revenue funds the next leap. This is how intelligence scales and becomes a foundation for the global economy.”

However, as I explored in “Two Tales of Compute,” we must distinguish between training compute and inference compute. Training is the upfront capital expenditure that requires thousands of GPUs running continuously for weeks to create a foundation model. Inference is the operational expense, the per-query cost of actually serving that model to users. Training compute is where the compute arms race lives. Inference compute is where the economics ultimately resolve.

The flywheel described by Friar overlooks a critical variable: compute payback. This is the time it takes for revenue to recoup investments in R&D and infrastructure (i.e. training compute, not inference). For LLMs to reach path to profitability, “payback” periods are expected to compress significantly through both better absorption and (training) efficiency gains, turning brute-force scaling into a race for better ROI per watt rather than more watts overall.

If the Equation Holds, Musk Wins

This leads to an uncomfortable truth that Friar’s disclosure inadvertently illuminates: if her equation is correct, then Elon Musk’s xAI - not OpenAI - has seized the high ground.

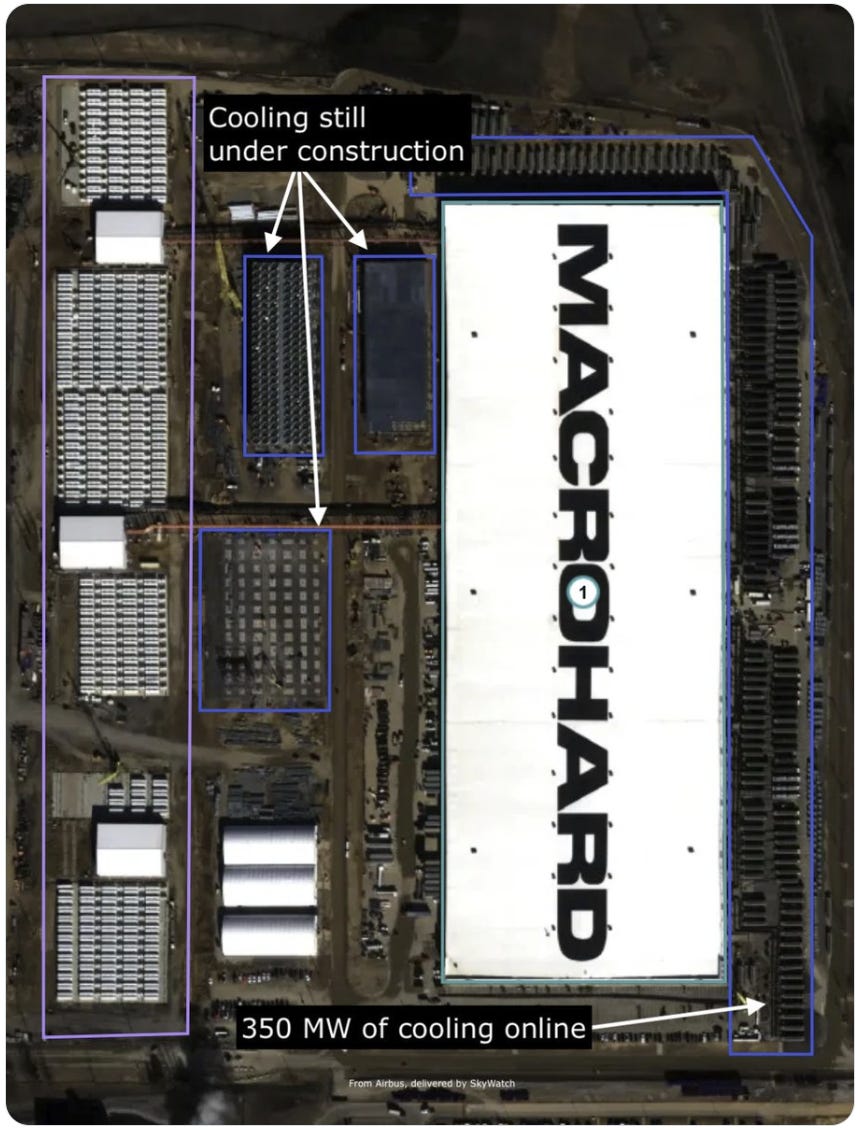

On January 17, Musk announced that Colossus 2 had become operational at 1 GW capacity, rendering it the first gigawatt-scale AI training cluster in history. By April, it will reach 1.5 GW. By mid-year, 2 GW. At full deployment, Colossus 2 will consume more electricity than the peak demand of San Francisco, a city of 870,000 residents, reduced to a rounding error in the power budget of a single machine learning facility. However, satellite analysis suggests that current cooling capacity is only ~350 MW, implying it may not yet be at full 1 GW - potentially ramping up. But still.

Using Friar’s arithmetic, at 1 GW, xAI should theoretically command $10 billion ARR. At 2 GW, $20 billion or beyond. However, current analyst projections for xAI remain more conservative. Standalone revenue estimates range from $2 billion to $15 billion for 2026.

And yet, xAI is building infrastructure as if Friar’s MRE rule had conclusively proven. With $20 billion in fresh Series E funding (upsized from an initial $15 billion target), xAI is deploying capital at approximately $1 billion monthly to train Grok 5, a rumored 6-trillion-parameter model built on mixture-of-experts architecture.

If the megawatt-compute-revenue calculus theorem holds, xAI has certainly been demonstrating remarkable execution on the physical execution side of the ledger.

Colossus 1 progressed from site preparation to full operation in 122 days, a timeline that would strain credulity at any other technology enterprise. Colossus 2 crossed the 1 GW threshold while competitors remain occupied with roadmaps targeting 2027. The distinction is not merely one of pace but of strategic architecture. Musk has systematically circumvented every bottleneck that imperils his rivals:

Grid constraints: xAI deployed Tesla Megapacks and procured on-site gas turbines to operate independently of utility infrastructure. When a 150 MW substation threatened to delay the original Colossus build, Musk engaged VoltaGrid for immediate capacity rather than await grid connection.

Permitting obstacles: When Memphis regulators balked at approval timelines, xAI acquired a former Duke Energy generating station across the state line in Southaven, Mississippi, filing permit applications in both Tennessee and Mississippi simultaneously. This was regulatory arbitrage executed on continental scale.

Supply chain bottlenecks: The company secured Nvidia allocations years in advance and now commands 67 per cent of Solaris Energy Infrastructure’s 1,700 MW turbine order book, effectively cornering a critical input market.

This infrastructure blitzkrieg represents a level of vertical integration not witnessed since the early decades of industrial electrification, when firms such as Insull’s Commonwealth Edison constructed generating capacity, transmission networks, and end-user relationships as unified systems.

OpenAI’s position appears less assured.

The company has intentionally taken a more deliberate and intricate approach to building needed compute, perhaps driven both by necessity (being a startup) and opportunity (being a red-hot startup). Friar framed OpenAI’s approach as a sophisticated, mature hedge to balance the risks of overbuilding and underbuilding.

“This system requires discipline,” she wrote. “Securing world-class compute requires commitments made years in advance, and growth does not move in a perfectly smooth line. At times, capacity leads usage. At other times, usage leads capacity. We manage that by keeping the balance sheet light, partnering rather than owning, and structuring contracts with flexibility across providers and hardware types. Capital is committed in tranches against real demand signals. That lets us lean forward when growth is there without locking in more of the future than the market has earned.”

True, perhaps. But it also places the fate of the company in the hands of a large stable of partners whose interests may align and diverge from time to time.

Consider the Stargate campus, the joint venture with Microsoft and Oracle, projected to achieve gigascale capacity, announced with such flourish about one year ago. It remains partially constructed and contingent upon partnership execution. The Stargate facility in Abilene, Texas - built by Crusoe Energy and currently under expansion by the company - has already encountered reported permitting delays, with potential for further setbacks amid labor and material shortages that have impacted similar AI infrastructure projects.

Should such delays snowball across the data center portfolio, pressure will intensify.

Realizing OpenAI’s $30 billion 2026 revenue target demands scaling from 1.9 GW to somewhere between 5 GW and 10 GW per experts, while simultaneously managing an estimated $19 billion in annual cloud expenditure and navigating the legal complexities of the organization’s nonprofit-to-profit conversion.

Looking back on the past three truly astonishing years that OpenAI has experienced, Friar noted with justified pride the company’s success so far: “This is never-before-seen growth at such scale.” But she also made the kind of admission that OpenAI couldn’t afford to make down the road as a public company:

“And we firmly believe that more compute in these periods would have led to faster customer adoption and monetization.”

OpenAI already faces a daunting scaling challenge to meet revenue projections. And to be fair, it’s far from alone when it comes to reaching the numbers needed to rationalize extraordinary capital expenditure.

Pulling the plug on scaling

All of these hopefuls face another reality check: the grid. Friar’s equation presupposes uninterrupted access to perpetually expanding power supplies. In this framework, megawatts function not merely as a convenient metric but as the singular point of failure.

Texas’s grid operator, ERCOT, has effectively declared the state fully allocated for large-scale data center interconnections through the remainder of the decade. And this is in the jurisdiction most aggressively courting AI investment, where Governor Abbott has positioned the state as the natural home of American compute infrastructure. Virginia’s Dominion Energy confronts analogous capacity constraints in the Ashburn corridor, historically the nation’s densest concentration of data center activity.

While energy is a variable for all hyperscalers, the impact is not necessarily the same. This context reveals xAI’s vertical integration as conferring a secondary advantage beyond mere velocity: optionality.

Musk owns the turbines. He retains the capacity to curtail their operation should efficiency gains obviate the requirement for such scale. Megapacks can be redeployed to alternative applications. Gas turbines possess resale value and can be physically relocated. The Memphis facilities retain worth as industrial real estate irrespective of AI demand trajectories. xAI has wagered on the Friar Equation whilst preserving an exit should the equation fail.

OpenAI has emulated Musk’s approach by ordering 29 gas turbines capable of generating 986 MW. That’s sufficient for approximately half a million GB200 NVL72 accelerators. But such equipment carries lead times of 12 to 36 months. The grid cannot rescue them. The turbines may not materialize in time.

OpenAI and Microsoft cannot execute a pivot equivalent to xAI’s. Multi-decade Azure and Oracle contractual commitments lock in capacity obligations regardless of whether such capacity proves necessary. Should edge inference and algorithmic efficiency consume the workloads presently routed through centralized training infrastructure, Stargate risks designation as the most expensive white elephant in technological history.

And this may not be an isolated case.

As I argued recently in my examination of Meta’s nuclear pre-commitments, including 6.6 GW of baseload power locked in through arrangements with Oklo, TerraPower, and comparable ventures, firms committing to decade-horizon power agreements are implicitly wagering that algorithmic innovation will remain subordinate to raw scaling through the mid-2030s. Oklo’s 1.2 GW tranche arrives in 2034, eight years hence. That represents a substantial interval during which efficiency gains could render such capacity superfluous. Beyond energy, the list of real-world obstacles continues to grow. I try to avoid politics here, but I’ll mention the growing pushback against such projects at the local level. Approximately $64 billion in announced US data center projects have been cancelled or materially delayed since 2023, victims of permitting disputes and community opposition. Amazon has publicly acknowledged that transformer shortages are retarding hyperscale construction in Virginia and Ohio. Oracle has deferred developments by as much as twelve months owing to skilled labor scarcity and materials procurement failures.

As David Cahn of Sequoia Capital has observed, 2024 represented the year of project announcements; 2025 witnessed construction investment flowing into GDP figures; 2026 constitutes the year of reckoning, when promised capacity either materializes or delays cascade through the system. Building physical data centers becomes a moat.

Amid the AI euphoria of the past two years, it was easy to forget that a data center is emphatically not a GPU cluster with an extension cord. It comprises a symphony of industrial inputs. Generators, cooling apparatus, switchgear, transformers, cabling, and prefabricated electrical assemblies - required to operate these facilities each carry lead times denominated in years rather than months. The suppliers serving AI hyperscalers confront their own capital expenditure decisions regarding factory capacity expansion. “If hyperscalers begin to warehouse their new AI chips rather than installing them directly into data centers,” Cahn has noted, “this will be a telltale sign that the era of delays has begun.”

Even xAI faces material regulatory exposure. The Environmental Protection Agency and affiliated advocacy organizations have targeted its unpermitted gas turbines in Memphis, alleging Clean Air Act violations. Should regulators compel compliance, xAI’s vertical power advantage diminishes accordingly.

Second vulnerability: algorithmic efficiency as a deflationary force

The most consequential threat to the Friar Equation emanates not from a competitor commanding superior GPU inventories but from one deploying superior mathematics.

DeepSeek, the Hangzhou-based laboratory founded by quantitative trading pioneer Liang Wenfeng, ended 2025 with a research publication that may ultimately prove more significant than any infrastructure announcement. The technique is known as the Manifold-Constrained Hyper-Connections, or mHC. It addresses a critical obstacle in scaling large language models: the numerical instability that emerges as networks grow deeper. By constraining information flow to a mathematical manifold, mHC enables architectures of considerably greater richness with a hardware overhead of merely 6.27 per cent. (I discuss mHC in my MiniMax IPO teardown.)

DeepSeek V4, anticipated around February 17 to coincide with Lunar New Year, will reportedly integrate mHC with the firm’s newly published “Engram” conditional memory architecture, disaggregating static memory retrieval from dynamic reasoning through O(1) complexity lookups, contrasted with the quadratic scaling characteristic of conventional attention mechanisms. For extended contexts exceeding one million tokens, the efficiency differential becomes transformative. DeepSeek’s mHC paper is the industry’s “black swan.

Such innovations highlight why compute payback provides an alternative lens to MRE. By measuring how quickly gross profits recover training compute costs, it exposes the hidden fragility of “brute-force” scaling, proving that a gigawatt-scale infrastructure is a stranded asset if a competitor achieves the same intelligence through superior mathematics at, for example, one-tenth the price.

Chris Hay, an IBM Distinguished Engineer, characterized mHC as a potential paradigm shift: “Model training is the expensive part. With this innovation, DeepSeek is saying, ‘how do I get more bang for my buck during pretraining?‘”

Should DeepSeek V4 achieve GPT-5 caliber reasoning at one-eighth the compute expenditure (as certain internal benchmarks reportedly suggest), the Friar Equation does not merely bend. It shatters. If 200 MW can abruptly generate the intelligence output of 1.6 GW through architectural innovation, every gigawatt-scale facility becomes a monument to superseded assumptions.

Anthropic already anticipates this decoupling. With projected 2026 revenue above $20 billion, an estimated compute foundation of 2-3 GW, Claude’s developer extracts markedly superior revenue per watt than Friar’s equation would predict - evidence that algorithmic discipline can substitute for brute electrical capacity.

The verdict

Friar’s megawatt-to-revenue disclosure constitutes carefully crafted narrative engineering. It attempts to transmute AI infrastructure expenditure from speculative research and development into industrial economics with calculable returns. It wants to assuage investor anxiety regarding burn rates by anchoring capital intensity to revenue scaling.

But the equation falls apart under the most facile scrutiny.

If the linearity holds, xAI’s execution advantage positions Musk to capture the value OpenAI’s own framework implies. If physical constraints bind, the promised gigawatts fail to materialize - and the revenue projections accompanying them prove equally phantasmal. If algorithmic efficiency advances at historical rates, the equation inverts entirely.

Second, and perhaps even more important, this goes to the mental adjustment required to navigate the ongoing discontinuity that is obliterating the old tech economy paradigm and familiar benchmarks that have served as reliable guideposts for so long. At such moments, it is tempting to grasp at any idea that seems to offer a sense of orientation.

In this case, the fragility in OpenAI’s framing is elemental. Intelligence is treated as a commodity akin to aluminum, where additional electricity invariably yields additional product.

We are grappling with an intelligence that potentially promises exponential transformation and yet may be constrained by the physical world.

Anything that sounds like a simple equation for neatly calculating valuation in that scenario is undoubtedly a trap.

This analysis extends “Beyond the Power Crunch: Meta’s Nuclear Gambit”, published a fortnight ago on Decoding Discontinuity.