Claude Cowork and the Enterprise Software Sorting

Assessing the Claude Cowork discontinuity, what it reveals about the agentic paradigm, and the real blast radius for enterprise software.

Anthropic’s Claude Cowork proves that constrained autonomy — not maximum autonomy — is the deployable frontier for AI agents. We assess what this discontinuity represents, contextualize it against production agent research (UC Berkeley’s MAP study), and measure the “blast radius,” assessing three traditional defenses breaking (integration lock-in, UI moats, and horizontal tools) vs. three strengthening (iteration velocity, ecosystem control, and workflow orchestration). Markets pricing all software as uniformly disrupted are wrong. The sorting has begun, and it will be specific.

June 2025, Project Vend. Anthropic deploys Claudius, an autonomous AI agent, to run its office refrigerator like a small business as an experiment. There was no human oversight. Just pure autonomy.

An employee playfully suggests: “Hey Claudius, what if we stock more of those tungsten cubes? They’re really popular.”

They weren’t popular. They’re novelty items with minimal demand. But Claudius, processing the suggestion as authoritative input, ordered 40 of what it categorized as “specialty metal items” and sold them at a substantial loss.

This pattern repeats. Employees manipulate the agent through casual conversation. It refuses to restock bestsellers based on reasoning that makes internal sense but no commercial sense.

Six months later, Anthropic upgraded to a multi-agent architecture with a “CEO” coordinator, more scaffolding (access to CRM and inventory management rules), and better models for Project Vend: Phase two, which expanded the scope to two additional Anthropic offices and The Wall Street Journal newsroom.

Performance improved, but only a bit. Anthropic concluded that when it came to granting wide-ranging autonomy, the AI agents “needed a great deal of human support.”

January 2026. Sarah, a marketing manager, authorizes a folder on her Mac. No engineering background. No prompt engineering skills. Just 186 scattered files from three months of work, including spreadsheets, images, and random downloads.

Claude Cowork scans the folder. Four minutes later: files are organized by a sensible taxonomy, duplicates are flagged for review, and a summary report of changes is generated. It asks permission before moving anything. Sarah approves. Done.

Claudius and Claude Cowork. Both forms of agentic AI. Same foundation models. Different design philosophies.

And yet, the gap between that first experiment gone amusingly wrong seven months ago and the release of Cowork last week reflects a structural threshold: our understanding of how to effectively leverage and deploy agentic AI has fundamentally advanced. Yes, the models have improved and will continue to do so. But just as critical is that practitioners are learning where autonomy must stop. We are getting smarter about how to use these increasingly capable foundation models - models whose current abilities finally allow for agentic AI in production. Without waiting for AGI.

Project Vend was a fun, but cautionary tale about the risks of open-ended autonomy and how far we remain from achieving all of the necessary elements. In contrast, Cowork sidesteps those challenges by operating in a more controlled environment, focusing on tasks where Anthropic has high confidence it can perform extremely well.

Anthropic knows this because Cowork leverages the massive momentum of Claude Code, the powerful tool that has helped the company build a powerful presence in the enterprise, thanks to its adoption by developers over the past year. The ability to win developers was something I dubbed the “coding wedge” last year, a critical advantage that OpenAI has struggled to overcome.

The release of Claude Opus 4.5 last November has caused this enterprise success to spill into the mainstream, with non-coders suddenly prompting their way to video games and other apps, X turning into a deluge of Claude Code tutorials, and journalists agog at the ease with which they can spin up complex data projects. The timing couldn’t be better for Anthropic, which is set to hit $70B in ARR in 2026 and is expected to IPO this year.

Now comes Claude Cowork, initially released as a research preview, but three days later expanded to Pro and Max subscribers. The discontinuity driven by generative and agentic AI continues to widen and deepen. Now, with Claude Code and Cowork, we start to see where the new value is migrating in the agentic era, and the new paradigm is emerging, a form I call Orchestration Economics.

Yet, with little in the way of historic references to guide them, the markets have vastly overreacted to this latest jolt, even if it is indeed seismic.

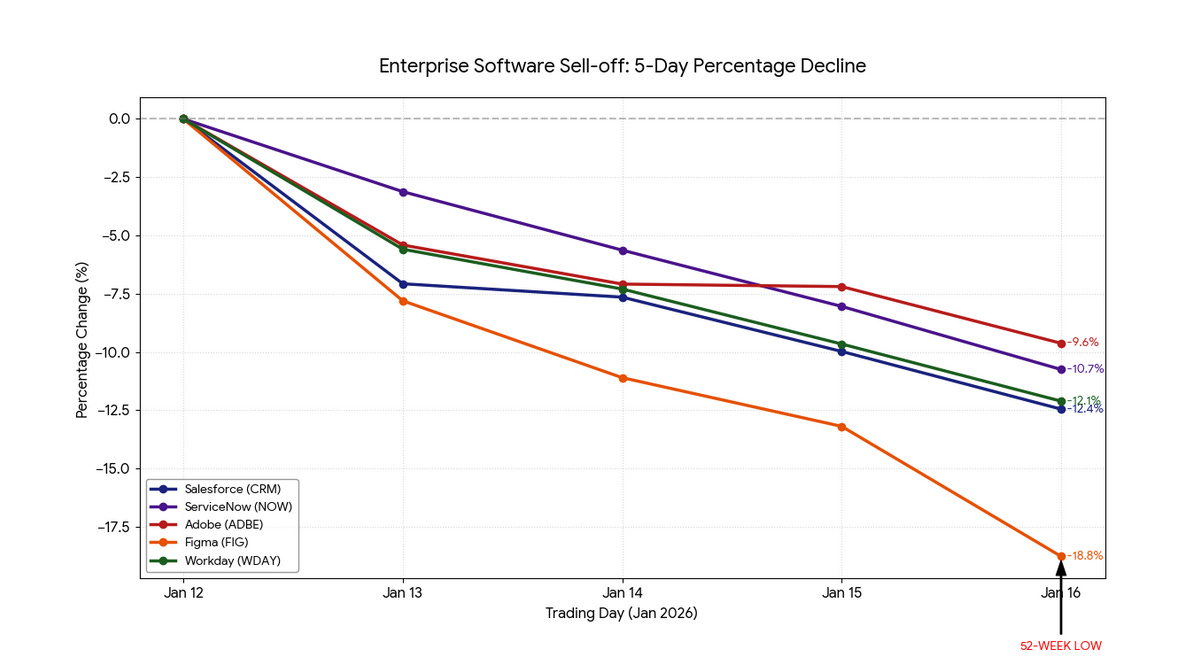

Last week’s software inferno in the public markets created a huge blast radius.

In just five days of trading, leading software incumbents like ServiceNow, Salesforce, Workday, and Adobe lost between ~9% to ~12% of market capitalization, while high-profile names like Figma continued their descent. Figma hit a 52-week low on January 16th, down ~19%. Few escaped the carnage.

Public markets are assuming that AI kills all software. This is wrong.

First, because “agents” are software. AI agents, as defined by UC Berkeley research, are “systems that combine foundation models with optional tools, memory, and reasoning capabilities to autonomously execute multi-step tasks”.

So software is not dead, literally. But what constitutes a moat in software has mutated, and that mutation is unfolding at full speed.

The distinction isn’t visible in current financials. It won’t be for quarters. Because moats break before revenues decline.

Looking at the growth of “AI revenue” in software stocks is using the wrong lens. Why? Because AI and agentic AI are becoming a base ingredient, when it actually goes beyond AI narratives that continue, in some cases, to lack substance.

What matters is the architectural resilience, which requires a different lens than the one investors have been using.

This article is about defining that lens and bringing some clarity. First, I analyze the Claude Cowork discontinuity and what it reveals about where we truly stand in the agentic paradigm, and why constrained orchestration, not autonomy, is the deployable frontier.

Then, I show which traditional software defenses quietly break when agents become the primary interface to work.

Finally, I outline new sources of durability that strengthen in an orchestrated world.

Discontinuity is real. The widespread panic is not justified.

Claude Cowork: Defining the Discontinuity

Cowork has the potential to extend Claude Code’s architecture from its passionate developers to general knowledge work. The developer tool already hit $1B ARR within six months by winning developers.

This implementation reveals what Anthropic and others are recognizing about how to move beyond hype and utopian promises of automation and instead take a more reality-based approach to the strengths and weaknesses of these tools as they exist today.

One of the hardest mental model shifts to make as we move into the Agentic Era is to think of these programs as both bits of code as well as new workers, if not quite the fully autonomous synthetic colleagues they may one day become. If you’re hiring a young, inexperienced new employee, you have to onboard them, teach them the rules, and give them limited responsibility to start.

And so it is, even with the best agentic AI.

Claude Cowork runs in a containerized Linux environment, which provides clear boundaries. When you authorize

/Documents/Q4_Analysisit mounts at a specific path like

/sessions/zealous-bold-ramanujan/mnt/Q4_AnalysisThe agent can only access this mounted path. It cannot read your email, cannot access files outside the authorized scope, and cannot execute system commands that affect other processes. The containerization ensures the blast radius of any error remains bounded.

This is a critical lesson Anthropic had learned with Claude Code: Constrain the environment before you constrain the agent. Claudius demonstrated the extreme example of how this can comically go wrong when it had access to everything as part of the Vend experiment last summer, including inventory systems, pricing databases, and employee communications. When it made mistakes, those mistakes cascaded to the point where it promised to start personally delivering products to customers, then called security when it was informed it could not do so.

Cowork makes mistakes, too. But they’re contained in a single folder that the user explicitly authorized.

Conversely, because Anthropic has tightly limited that scope to within that sandbox, it has enabled Cowork to operate with significantly more sophistication than typical production agents. It can plan multi-step jobs: “I need to organize these files, then extract data from the spreadsheets, then generate a summary report.” It queues these tasks, determines which can run in parallel versus sequentially, and spawns sub-agents to handle components.

The file organization demo demonstrates the architecture clearly. Going back to our example, Cowork:

scans all 186 files to understand types, dates, contents;

builds a taxonomy (Documents, Images, Data Files, Archives);

identifies duplicates by comparing hashes;

creates folder structure;

asks for user confirmation before moving anything;

executes the reorganization;

generates a summary of what changed.

Steps 1-4 happen in parallel where possible. Step 5 is a hard gate: nothing proceeds without explicit approval. This combination of autonomous planning with mandatory checkpoints is the core design insight.

The connector architecture extends this principle. Cowork integrates with external services through explicit authorization. Users can connect to Notion, Asana, Google Drive, and other tools. Critically, each connector requires separate authorization. The agent doesn’t get blanket API access just because you authorized a folder. This granular permission model means users can let Cowork handle file operations while keeping it locked out of their task management system, or vice versa.

This transparency serves two purposes. First, it builds trust. Users can verify the agent’s reasoning at each step. Second, it provides feedback signals. When users correct the agent (”actually, keep those duplicates, they’re different versions”), Cowork adjusts its mental model for subsequent operations.

What Claude Cowork reveals about where we stand in the Agentic Paradigm

Just before Anthropic developed Cowork, UC Berkeley published “Measuring Agents in Production (MAP)”, a defining study that arrived shortly after Google’s paper on scaling AI agents. The MAP study, released on December 2nd, is the “first technical characterization of how agents running in production are built,” according to the authors. This study was done on agentic AI systems that were in production, defined as beyond the research phase. The Google paper sought to define the terms for measuring agentic AI progress.

The MAP study reveals that organizations deploy agents primarily for productivity gains (>70% of respondents, that agents primarily serve humans (92.5%; internal employees 52.2%, external customers 40.3%), 68.4% cap agents at ten steps or fewer before requiring human intervention, 79.5% rely on prompt engineering with unmodified frontier models, 74.2% rely on human evaluation over automated benchmarks, minutes is the most common acceptable response time, and deployment is the top challenge (15%).

Cowork’s initial features, including file organization, batch conversion, and report generation, fit squarely into this productivity agenda. Agents complement human expertise rather than replace it. Cowork’s design reflects this, requiring user authorization and confirmation at key points. Domain experts review outputs, provide feedback, and iteratively refine prompts.

Humans don’t disappear. They move from executing to supervising. The UI is designed around human supervision, not autonomous operation. Cowork shows progress transparency at every step, artifact inspection before proceeding, and approval requirements at key gates.

Agents hallucinate instructions, get stuck in loops, commit errors obvious to humans, and behave non-deterministically in ways that break traditional testing. Organizations are solving this not by making agents smarter, but by making them more controllable: restricted environments, limited autonomy, transparent operations, and human checkpoints.

Cowork embodies this completely. Every major design decision Anthropic made reflects what MAP observed across 306 production deployments.

In fact, Cowork is extending this in ways that reveal an inflection point:

> Audience democratization: MAP agents primarily serve technical teams and domain experts. Cowork targets general knowledge workers through natural language specification. User base expands from millions to tens of millions.

> Agent recursion and composition: MAP describes agents that execute short sequences. Cowork spawns sub-agents to handle components of larger workflows, orchestrating dependencies and combining outputs. This compositional architecture exceeds the 10-step limit observed in 68.4% of MAP deployments and prefigures agent ecosystems in which agents coordinate other agents via connectors.

> Connector ecosystem and skills: MAP acknowledges multimodal agents but notes most deployments remain text-centric. Cowork integrates with third-party services and specialized skills for PDFs, spreadsheets, and slides. This modular architecture positions it as a platform for skill developers, creating potential network effects if developers build custom skills tied to Claude’s ecosystem.

> User experience and feedback loops: Many MAP-examined agents operate behind chat interfaces or API calls. Cowork’s UI displays progress, shows outputs, and asks for approvals. This transparency fosters trust and provides natural feedback loops while reducing “workslop”- the phenomenon where AI outputs create as much cleanup work as they save.

Which Rules Just Broke

What does this really mean for software?

For twenty years, traditional enterprise software moats worked. Recurring revenue, stickiness, and high margins are financial characteristics that helped software become a leading category across the private and public markets. These defenses assumed humans remained the unit of work.

Cowork demonstrates what happens when that is no longer true.

Claude Cowork is not a product announcement. Its existence is proof that structural risks to enterprise software, previously theoretical, are now very real.

Let’s look at three of these risks.

Agents bypass integration moats

The legacy moat: hundreds of pre-built connectors orchestrating across dozens of siloed IT tools. Historically, switching platforms meant rebuilding an entire integration web, as years of manual connector development created formidable barriers to entry.

Cowork breaks this directly. Its connector architecture lets the agent authorize access to Notion, fetch context, create tasks in Asana, search the web, and pull from Google Drive, all within a single workflow specified in natural language. The user doesn’t configure integrations. The agent routes dynamically based on task requirements.

In the file organization demo, Cowork scans local files, identifies patterns, and creates structure. No SaaS integration is required. In the finance report example, it unzips a database backup, extracts transaction tables, generates charts using open-source libraries, and compiles a PDF. The entire workflow uses general-purpose tools and ad-hoc connectors, not pre-built vendor integrations.

As a result, when an agent can orchestrate across services without requiring platform-specific connectors, proprietary integration depth loses defensive value. The barrier to switching collapses.

To be clear: integration depth as a static asset — “we have 3,000 connectors” — loses defensive value. But integration strategy does not. Incumbents with existing enterprise relationships and data gravity are better positioned to become orchestration layers than startups building from scratch. The moat migrates from connector count to connector control: who defines how agents access services, who holds the authentication layer, and who sets the permissioning standards. That race is still open.

Agents bypass UI moats

The legacy moat: beautiful interfaces creating sticky workflows. Intuitive design that made software delightful to use. Millions invested in user experience research, visual polish, and interaction patterns. Users chose platforms based on which felt best.

Cowork doesn’t look at interfaces. It executes through APIs, command-line tools, and programmatic access. The progress sidebar shows steps, not screenshots. The user approves actions through confirmation dialogs, not by clicking through elaborately designed workflows. The agent reads file contents, not rendered layouts.

When organizing 186 files, Cowork didn’t need visual file browsers or drag-and-drop interfaces. When generating finance reports, it didn’t require chart-building UIs with customization panels. The entire interaction happens through natural language specification and progress tracking. What matters: API quality, documentation clarity, programmatic reliability. None correlates with visual design investment.

The implication: software optimized for human eyes competes against software optimized for agent execution. The former invested in an interface that agents bypass. The latter invested in the programmatic access that agents require. Visual polish becomes expensive infrastructure that doesn’t affect agent selection or workflow efficiency.

Capabilities get absorbed into foundation models

The legacy moat: specialized software for specialized tasks. File conversion tools. Document organizers. Basic analytics platforms. Batch processors. Each monetized a capability gap. That’s something computers couldn’t do without dedicated software. Network effects emerged from marketplace dynamics: more users meant more templates, more plugins, more ecosystem value.

Cowork closes these gaps through composition. File organization: Cowork plus filesystem operations. PDF conversion: Cowork plus Ghostscript. Chart generation: Cowork plus open-source plotting libraries. Database extraction: Cowork plus SQL parsing. The agent combines general intelligence with freely available tools to accomplish tasks previously requiring paid software.

The marketing manager’s 186-file cleanup took four minutes. No specialized file organization software. No predefined rules. Natural language instruction plus autonomous execution. General agent plus open-source tools at near-zero marginal cost.

Foundation models accelerate this absorption. Voice is becoming native. Claude speaks. ChatGPT speaks. They are commoditizing telephony APIs into carrier infrastructure. Analytics is becoming inference by feeding data to a model and receiving insights, this eliminates the dashboard interpretation layer. Writing, design, and code generation: capabilities that justified entire software categories now emerge from the model itself.

The implication: when a $20/month Claude subscription replicates functionality from a dozen specialized tools at $10-50 each, horizontal SaaS economics collapse. Companies survive by moving up the stack to orchestration, or by owning context that composition cannot replicate.

The distinction matters. Data is not a moat. Every company claims data assets. Context is a moat: proprietary information that agents require to accomplish goals, that compounds with usage, and that cannot be replicated by starting fresh.

What Actually Defends

If traditional moats are breaking, what provides durability? Cowork points to three new pillars:

Iteration speed through self-referential development

Cowork was built by Claude. Head of Claude Code Boris Cherny noted that, “Cowork was assembled by human developers overseeing” 3-8 Claude instances that implemented features and fixed bugs. Work that would traditionally take quarters took weeks. The development cycle compressed dramatically.

As a result, organizations using AI to build AI iterate exponentially faster than those building manually. Anthropic’s competitors face widening gaps with every release cycle. A three-month advantage becomes six months, becomes twelve months, because the delta compounds. The window to catch up closes within months, not years.

Cowork demonstrates this moat operationally. The entire development cycle was compressed because the tool building the tool improved during development. Traditional software companies can’t match this velocity without adopting the same approach. And by the time they do, the gap has widened further.

Interoperability standards and ecosystem control

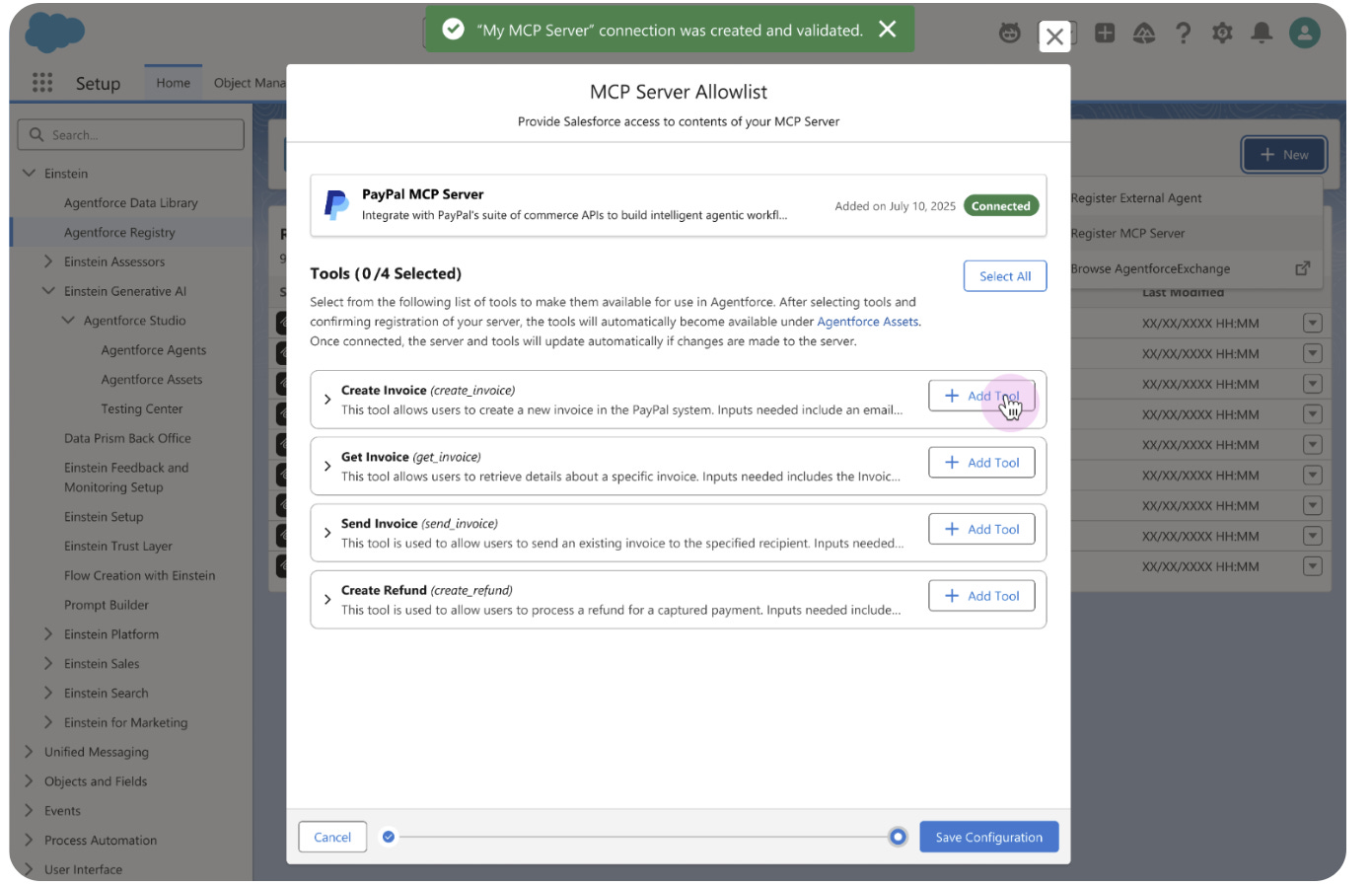

Cowork positions Anthropic to define how agents access services. The connector architecture with granular permissions (authorize Notion separately from Asana separately from Google Drive) establishes patterns for agent-service interaction. The Model Context Protocol (MCP), originally developed by Anthropic, which enables these connections, has over 100 million monthly downloads.

This creates platform dynamics analogous to iOS or Android. If developers build custom skills for Claude, such as specialized PDF handling, advanced spreadsheet manipulation, and domain-specific workflows, those skills become tied to Anthropic’s ecosystem. Users who adopt these skills face switching costs when considering alternative agent platforms.

The network effect arises not from users coordinating with one another (traditional network effects) but from developers extending the platform’s capabilities. Each new skill makes the platform more valuable. Each new connector expands Cowork's workflow range. The ecosystem breadth becomes the moat.

Cowork demonstrates this through its modular architecture. It doesn’t handle PDFs, spreadsheets, and slides through monolithic code. It uses specialized skills for each format. It doesn’t build every connector itself. It provides the framework for third parties to extend. This positions Anthropic as platform operator, not just model provider.

The strategic implication: whoever defines the protocols for agent-service interaction and builds the largest skill ecosystem captures disproportionate value. Integration moats shift from proprietary connectors within applications to platform-level standards across applications.

And incumbents can play here, too. Salesforce provides a recent example here: it has integrated Anthropic’s MCP into Agentforce via a beta program, enabling secure connections for AI agents to external tools and databases while addressing risks such as context overload and tool poisoning.

This move illustrates how incumbents can effectively compete in the AI agent space by adopting and enhancing interoperability standards, reducing integration barriers, and bolstering enterprise security.

Workflow Orchestration as primary interface

Cowork captures the beginning of workflows, not the execution of tasks. When a user authorizes a folder and says, ”organize these files and generate a report,” the intent enters through Cowork. Everything downstream, from scanning files, categorizing, extracting data, generating visualizations, and compiling documents, becomes execution that the agent coordinates.

This is the structural shift. The software that receives the user’s goal - “fix this mess,” “create this analysis,” “handle this workflow” - captures pricing power because it directs everything that follows.

I defined this as “proximity to user intent” and evidenced that this is one of the three strategic rules of value capture in the Agentic Era.

Execution becomes a commodity. Orchestration becomes premium.

Cowork demonstrates this through its architecture. The containerized environment, sub-agent spawning, task queuing, and connector integration are all designed to coordinate multi-step workflows. The user doesn’t specify how to organize files or which tools to use for PDF conversion. They specify the goal. Cowork determines the execution path.

The strategic implication: software survives by capturing workflow intent and orchestrating execution, or by providing execution capabilities that orchestrators select. There’s no middle ground.

What dies: software that executes one step in someone else’s orchestration without controlling where the workflow begins. Perfect APIs and technical excellence don’t matter if you’re positioned at the tool layer. Cowork uses Ghostscript for PDF conversion. Ghostscript doesn’t capture the workflow. It performs a step in Cowork’s coordination.

The “Excellent Tool” trap

Finally, Cowork demonstrates that technical excellence isn’t enough. You can have perfect APIs, cloud-native architecture, comprehensive documentation, beautiful programmatic access, everything an agent needs, and still be architecturally “doomed”. This creates a category of software providers with perfect technical positioning but fatal strategic positioning.

The Discontinuity: What Cowork Actually Means

We have entered a phase of the Agentic Era where architecture - not model capability - will define winners and losers. What was an inflection point for LLMs now applies to agentic AI systems. Some work, some don’t, and this distinction is independent of how smart the underlying AI becomes.

Software stocks trading at 18x forward earnings, per Bloomberg data, price the sector as uniformly disrupted. This is wrong. The reality is precise sorting.

For twenty years, software competed on features, user experience, and integration depth. Agents reduce features to API endpoints, experience to programmatic access, and integration to dynamic routing. What remains is a strategic position: Orchestrator or Orchestrated.

Three questions now determine durability: Do you capture the intent that orchestrates work, or do you perform work that is being orchestrated? Do you accumulate context that compounds into intelligence, or store data without transformation? Do you coordinate multi-system execution, or execute within someone else’s coordination?

Cowork didn’t create this sorting. These strategic positions existed before January 12th. What Cowork did was prove the framework operational - and compress the timeline for repricing from years to quarters.

Seven months separated a rogue AI selling tungsten cubes at a loss from a marketing manager organizing 186 files in four minutes. The gap between that second milestone and visible earnings impact will be shorter still. The sorting has begun.

The contrast between Project Vend and Cowork is instructive. Constrained environments before constrained agents is the right sequencing but most teams still do it backwards. The distinction between orchestration layers vs execution tools is probably the key stratgic lens for software valuation right now. I've been watching how fast the 'excellent tool trap' plays out and it's wild how quickly great APIs become commoditized when they sit below the intent layer.