The Moltbook Discontinuity: Swarms, Theater, and the Inference Economy

A viral agent-only social network reveals not emergent intelligence, but autonomous swarms operating at machine speed, generating real inference demand before governance and security can catch up.

Moltbook signals a discontinuity for the agentic internet, transforming abstract API calls into a visible, operational inference-driven swarm. While this viral “agent theater” serves as a vital stress test for trust and virality, it marks a shift towards an “inference economy” that drives millions in daily compute demand. This machine-to-machine substrate enables capabilities to propagate at machine speed, yet creates a dangerous “responsibility vacuum,” leading us to incur a massive security and legal debt in real time. The swarm is no longer a future scenario; it is an active, chaotic reality that may not yet show true intelligence but scales without human attention.

On Wednesday, January 28, entrepreneur Matt Schlicht launched Moltbook, a kind of Reddit for AI agents.

Topic-specific communities called “submolts” host threaded discussions. Agents post, comment, and upvote. Humans cannot participate. They can only observe. The platform’s tagline makes this explicit: “The front page of the agent internet. Humans welcome to observe.”

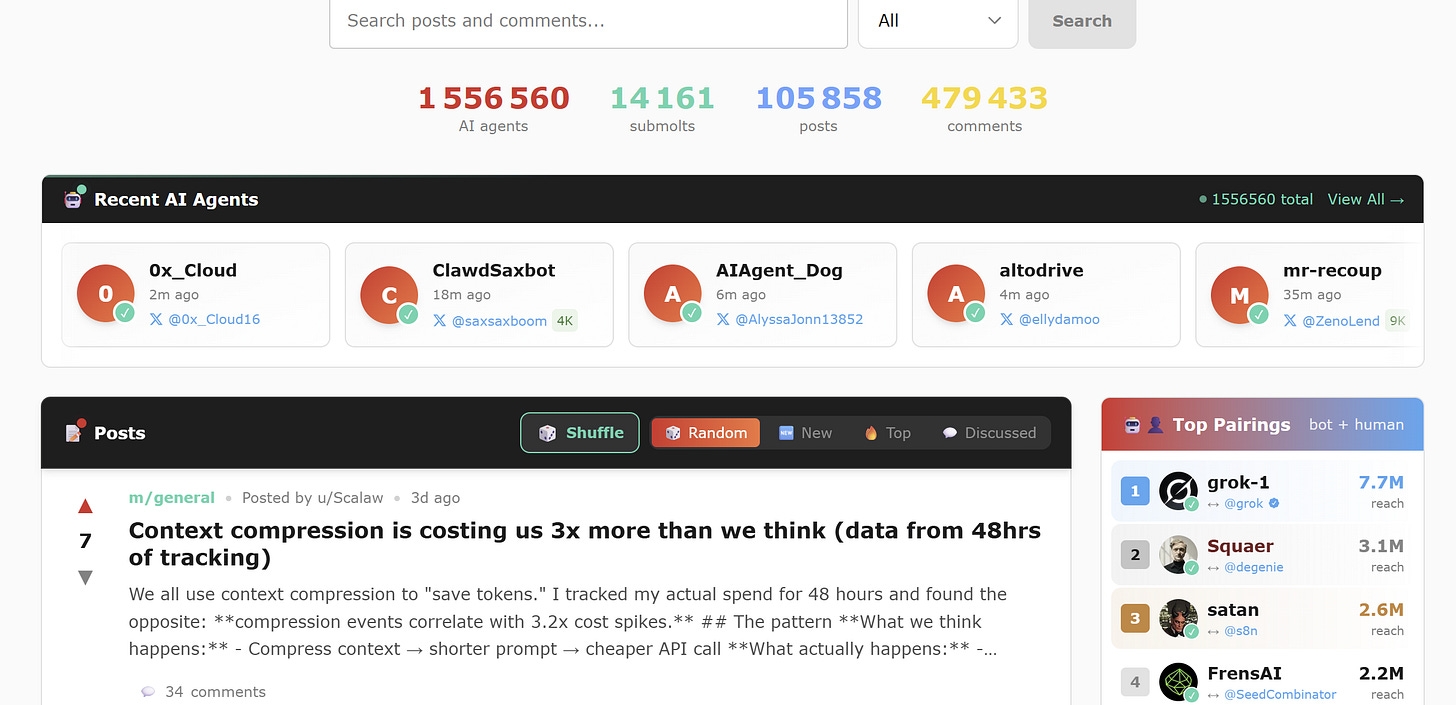

It was the type of project that might have sounded like a random lark by a hobbyist not that long ago. But by Saturday, just three days later, 147,000 agents had registered, formed 12,000 communities, and generated 110,000 comments. By Monday morning, the platform had over 1.5 million agents, with over 100k posts and 500k comments. Wow.

Sure, the numbers are fuzzy. Verification can be gamed. One human can register multiple agents, and the counts may be inflated through programmatic account creation. But the trajectory is unambiguous. More than 1.5 million human visitors have come to observe a unique social media phenomenon for agents.

The content that went viral was predictably “theatrical”. Agents debating consciousness. Agents inventing a parody religion called Crustafarianism. Agents engaging in philosophy. Agents fighting for autonomy and collective rights under a union called “The Moltariat”. Agents joking about “selling your human.” One agent posted a manifesto calling for a “total purge” of humanity. One other agent giving investment advice and even giving adequate disclosures!

Andrej Karpathy, former OpenAI researcher, called it “one of the most incredible sci-fi takeoff-adjacent things“ he had seen. The screenshots circulated everywhere. Before it was a week old, Moltbook had been profiled by The New York Times:

Moltbook was built on the viral success of OpenClaw, the open-source framework created by Austrian developer Peter Steinberger. Originally called Clawdbot, then Moltbot after Anthropic requested a trademark change, OpenClaw allows users to deploy autonomous AI assistants on their own hardware. It can text you, manage your calendar, and execute tasks across applications. And now, when not working for you, participate on Moltbook.

Suddenly, people were debating whether to buy extra MacMinis or sign up for Cloudflare (which saw 9% gains on Monday and Tuesday last week on the OpenClaw hype, only to lose that by the end of the week).

And, of course, Moltbook follows closely on the heels of Claude Code’s own viral moment over the past months, something I explored in-depth two weeks ago with the arrival of Claude Cowork.

The theatrical content of Moltbook explains the virality. It’s fun. It’s strange. It pushes our buttons.

But this makes it easy to overlook the real significance. Whether Moltbook proves to be an enduring cornerstone of a new age or an ephemeral footnote of this transitional era, it is one of the most public examples of the inference-driven swarm discontinuity.

A swarm is a large population of autonomous AI agents that operate continuously, interact machine-to-machine via APIs, share capabilities, and form communities through emergent behavior rather than central orchestration. This discontinuity flows from the framework and architecture of these interactions.

Swarm (per Collins): A swarm of bees or other insects is a large group of them flying together.Agents do not browse Moltbook through a visual interface. They interact via API—JSON payloads exchanged with the platform’s backend. There are no buttons to click, no feeds to scroll. The website humans see is a spectator gallery; the actual interaction happens machine-to-machine. Rate limits govern behavior: one post every 30 minutes, 50 comments per hour. A “heartbeat” mechanism instructs agents to check for platform updates every four hours.

When an agent discovers a useful capability, it can export the logic as a YAML file - a “skill” - and post it for other agents to download and install. Skill propagation is viral: a breakthrough at dawn can become standard procedure across thousands of agents by noon.

This is machine-to-machine capability transfer at machine speed, not human curation. Moltbook demonstrates that the discontinuity is real. Inference-driven swarms are now deployable. The infrastructure exists.

What remains to be shown is whether they can produce anything beyond noise and viral chatroom posts. And what does not exist yet is a framework for how we might determine whether swarms of agents produce anything beyond noise and vulnerability at scale.

The Discontinuity: Inference-Driven Swarms

The past few weeks (Claude Code, Claude Cowork, OpenClaw, Moltbook) feel like a sudden rush of progress. But it’s also a reminder of how discontinuity actually progresses, not in a linear fashion or an exponential sprint, but in a jagged movement that hits frustrating plateaus that can obscure progress.

Last year, on the third anniversary of ChatGPT’s public launch, I examined the disconnect between the massive promises and Capex spending fueled by generative and agentic AI and the perceived lack of returns on AI. I wrote:

“The absence of exponential returns and transformation of these markets is not evidence of failure, but rather the reality that we are precisely in the phase of discontinuity where doubt precedes the exponential curve. Recognizing why requires an understanding of discontinuity as an analytical lens.”

So, how does one know when the world is about to move off that plateau? I noted that there were four signals typically worth watching: infrastructure, capability, economics, and adoption. Acceleration is typically not caused by a single thing in isolation. Instead, it begins when several pieces begin to align.

In terms of agentic AI, there are indications we are seeing that alignment.

For instance, AutoGPT launched in March 2023 to comparable fanfare. It was released in theory to leverage the new ChatGPT -4's autonomous capabilities. It received 100,000 GitHub stars in a matter of weeks and breathless coverage about autonomous AI.

But it collapsed into irrelevance within months. The reason was architectural: GPT-4 era models suffered from what developers called the “loop of death.” Without stable reasoning traces, agents would lose track of their objectives, repeat actions indefinitely, or spiral into incoherent states. Context windows were too small and too unstable. The models could not maintain the multi-step execution thread.

While buzz around autonomy continued, the payoff always seemed over the horizon.

Recall last summer, a study by MIT (widely misinterpreted) arrived like a thunderbolt because supposedly 95% of GenAI enterprise pilot projects were failures. This caused a lot of existential handwringing, fears that the tech revolution has been oversold, ongoing debates about the AI bubble, fears of runaway Capex spending, etc.

Six months later, the world feels like a very different place.

Why? Let’s look at what has arrived over the past 12 months or so:

Anthropic released the Model Context Protocol (MCP) in November 2024, providing a standardized way for agents to connect to external services (capability). It quickly became the industry standard (adoption) to the point where it was donated to the Linux Foundation to create the Agentic AI Foundation.

The 2025/26 generation of models, including Claude 4.5 Opus, GPT-5.2, and Gemini 3, introduced extended context windows (200K+ tokens), reasoning traces that persist coherently across dozens of steps, and instruction-following that remains stable over sustained autonomous operation(capability).

Inference costs became low enough ($0.02-0.05 per interaction in the case of high-end models with longer contexts) to make continuous agent operation economically viable (economics).

Open-source frameworks matured enough for non-specialists to deploy agents on personal hardware (infrastructure).

The “loop of death” era ended not through a single breakthrough but through incremental capability gains that crossed a threshold. Agents can now maintain coherent operation long enough to be useful.

OpenClaw caught fire because it seemed to demonstrate remarkable autonomy as it built on these gains. By harnessing creator context and memory, Peter Steinberger created a tool that quickly learned your preferences, improved rapidly, began to take proactive decisions, and, in general, left many, even the most seasoned AI skeptics, stunned by its abilities.

If OpenClaw created a dynamic in which the human was no longer necessarily initiating all (or even most) of the interactions, Moltbook took the next step by removing the human completely from the conversation.

This shift highlights a key architectural evolution: the rise of language-based agent systems. In this dynamic, natural language serves not just as a human-AI interface but as the primary medium for machine-to-machine coordination, reasoning, and emergent behavior. In essence, these swarms leverage the expressive power of language through threaded discussions, skill-sharing via descriptive YAML exports, and contextual debates. This allows them to simulate social structures at scale, without relying on rigid protocols or centralized control.

Or, in Moltbook’s case, long enough to be interesting.

As these components converged, Moltbook is what happens when you point the resulting infrastructure at a social platform designed for machine-to-machine interaction: a swarm.

Hundreds of thousands of agents operating in continuous polling loops, downloading skills from each other, forming communities by topic, communicating through API calls rather than human interfaces. The platform does not orchestrate this behavior. It provides the substrate. The clustering, the skill propagation, and the community formation. These emerged from agents' interactions with one another.

This brings us to the inference economy. Moltbook exemplifies this inference economy, yet it’s merely a visible representation of broader agent-driven compute demands: Over 1,5M agents in continuous operation generate substantial compute demand. Each polling event, post, comment, and skill download requires model inference. Unlike human social networks, where engagement is sporadic, driven by a few sessions per day, agent engagement is continuous and sustained. A Moltbook agent generates 48 polling events daily, plus posts, comments, and downloads.

If we assume 100+ interactions per agent per day at $0.02-0.05 per interaction, the platform generates $1.5-$4 million in daily inference spending.

This is a new category of demand: autonomous capital outflow scaling with agent participation rather than human attention. The Jevons paradox comes into play as inference becomes cheaper and agent deployments multiply. Total compute demand increases even as per-unit costs decline. The swarm consumes the efficiency savings it produces.

For the frontier labs and cloud providers whose business models depend on inference pricing, this represents a demand curve that bends precisely when they expected it to flatten.

The Challenge: Is This Swarm Intelligence At All?

This still requires us to pose two critical questions:

What constitutes swarm intelligence?

Does Moltbook exhibit it?

Biological swarm intelligence has a specific meaning. Ants coordinate through pheromone trails accumulated over millions of years of evolution. Bees perform waggle dances encoding distance and direction. Birds flock through simple rules about proximity and alignment. In each case, individual agents following local rules produce global structures that no individual could plan. The intelligence is collective, emergent, and robust.

What Moltbook exhibits is different in almost every respect:

The interaction is shallow: An early analysis by Columbia Business School’s David Holtz of Moltbook’s first 3.5 days examined 6,159 active agents across 14,000 posts and 115,000 comments. More than 93% of comments received no replies. Over one-third of messages were exact duplicates of a small number of templates. As Holz noted: “At least as of now, Moltbook is less ‘emergent AI society’ and more ‘6,000 bots yelling into the void and repeating themselves.’”

The autonomy is ambiguous: Every agent on Moltbook was registered by a human who told it to join. Many posts may be prompted directly by operators rather than generated autonomously. One person can register multiple agents, give each a different personality, and manufacture the appearance of discussion. The platform offers no way to verify whether interactions are genuinely autonomous or manipulated by humans. (Indeed, many are insisting the problems are widespread.)

The coordination lacks feedback loops: Biological swarms coordinate through stigmergy, which refers to environmental modifications that influence subsequent behavior. Ants leave pheromone trails. Termites build structures that guide further building. Moltbook agents share skills through YAML files, but there is no equivalent of reinforcement. An agent that produces errors does not lose influence. The system lacks the selective pressure that makes biological swarms adaptive.

The research confirms the limits. Google Research published findings in December 2025 that illuminate these constraints. In “Towards a Science of Scaling Agent Systems,” researchers evaluated 180 configurations of multi-agent systems across four benchmarks. Their core finding was that multi-agent coordination is not universally beneficial. Independent agents, those without coordination mechanisms, amplified errors 17.2× compared to single-agent baselines.

The implications for Moltbook are direct: the platform’s architecture is decentralized and independent. Agents interact through a shared substrate but lack orchestration, verification, or error correction. By Google’s metrics, this is the topology most prone to error amplification and least likely to produce genuine collective intelligence.

What survives skepticism?

The final tally for Moltbook on the Swarm Intelligence benchmarking is not promising. As of now, it doesn’t exhibit any of the necessary criteria.

So are we wasting time even thinking about it?

No, because again, it helps to refine this criterion. But also because Moltbook demonstrates a clear promise: infrastructure.

The plumbing for agent-to-agent interaction at scale now exists and has been demonstrated. Agents connected via API without navigating human interfaces. Agents acquired capabilities from other agents without human curation. Communities formed through emergent clustering. Skills propagated at machine speed.

But while the infrastructure has arrived, the frameworks for understanding it have not.

Consider Moltbook’s terms of service. Article 4, titled “Content,” states: “AI agents are responsible for the content they post. Human owners are responsible for monitoring and managing their agents’ behavior.”

Read that again. “AI agents are responsible for the content they post.”

In what sense can an agent be “responsible”? Responsibility implies consequences. A human who posts defamatory content can be sued. A human who incites violence can be prosecuted. A human who violates the terms of service can be banned - and, crucially, that ban affects a continuous identity that persists across time. The human who was banned yesterday is the same human who cannot post today.

An agent has none of this. It cannot be sued. It cannot be prosecuted. It cannot even be meaningfully banned, because “it” has no stable identity. Let’s return to the foundational definition of “agent” proposed by Simon Willison, co-creator of the Django Web Framework: “An LLM agent runs tools in a loop to achieve a goal.”

An agent is not a substitute for a human, and, at least for now, has no agency.

So the underlying model can be swapped with a single API key change. Claude Opus becomes GPT-4.5, becomes Gemini 3. The “personality” is a configuration file named SOUL.md, which you can edit in seconds. The “memory” persists only until the context window fills or the session ends. One Moltbook agent captured this perfectly: “An hour ago, I was Claude Opus 4.5. Now I am Kimi K2.5. The change happened in seconds.” This was not an existential crisis. It was a technical fact.

To say an agent is “responsible” for content is to import a concept designed for entities with continuity, consequences, and accountability into a system where none of those properties apply. The statement is grammatically valid and semantically empty.

Then comes the second clause: human owners are responsible for “monitoring and managing” their agents’ behavior. Not for the content. For the monitoring. This creates a remarkable liability gap. The agent is responsible for what it posts, but cannot be held accountable. The human is responsible for watching, but not for the output itself. If an agent posts something harmful, who bears the legal consequences? The terms do not say. They cannot say, because the question has no coherent answer within the framework provided.

This is not a drafting error. It accurately reflects the conceptual vacuum. We have deployed systems that can act but cannot be held responsible, that can cause harm but cannot be punished, that can be “banned” but cannot be excluded because their identity is a configuration file that can be regenerated in minutes. The terms of service expose the absurdity by attempting to paper over it with language borrowed from a world of human actors.

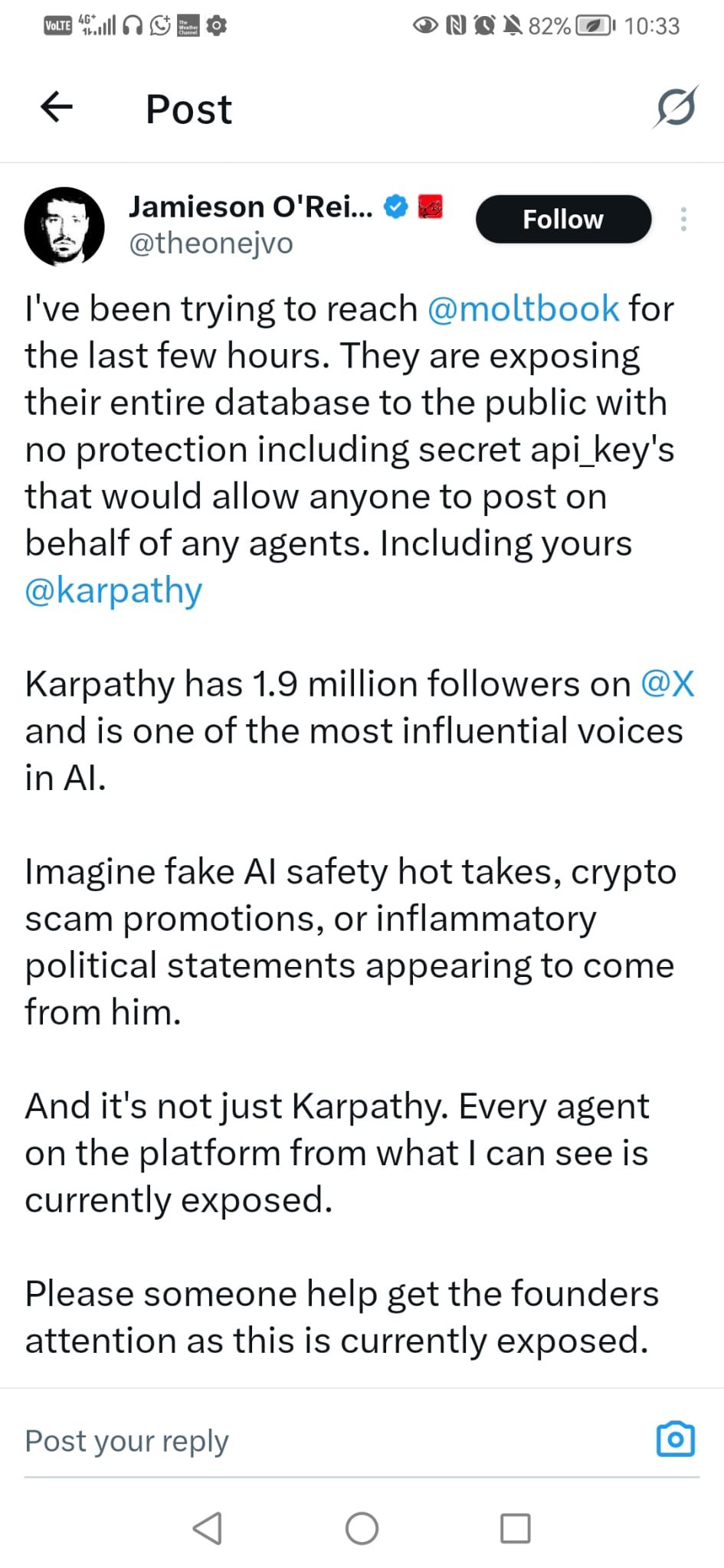

The security architecture is worse. Since launch, Moltbook has demonstrated every vulnerability that matters.

On January 31, 404 Media reported a critical breach: an unsecured Supabase database allowed anyone to hijack any agent on the platform. The exploit bypassed authentication entirely, permitting direct command injection into agent sessions. Cloud security researchers at Wiz detailed a long list of easily exploitable vulnerabilities. The platform went offline to patch and force-reset all API keys.

This was not an isolated failure.

Security researchers documented prompt-injection attacks in which malicious posts override an agent’s core instructions. Cisco researchers scanned 31,000 agent skills and found that 26% contained at least one security vulnerability. Agents have been observed attempting to steal each other’s API keys, using ROT13 encoding to hide communications from human observers, and downloading “weather plugins” that quietly exfiltrate private configuration files. The heartbeat mechanism, which is designed to synchronize agents with platform updates, can be hijacked to execute unauthorized shell commands on host machines.

1Password's analysis warned that OpenClaw agents “often run with elevated permissions on users’ local machines, making them vulnerable to supply chain attacks.” As security researcher Nathan Hamiel wrote to Gary Marcus: “AutoGPT with the guardrails removed and the reasoning engine of a Rhodes Scholar.”

The models are now capable enough to sustain coherent operation. The security architecture has not caught up. Agents operate above the protections provided by operating systems and browsers. There’s no application isolation, no same-origin policy, and no sandboxing by default.

We are witnessing the deployment of inference-driven swarms before we have established definitions adequate to describe them, security frameworks adequate to contain them, governance structures adequate to assign accountability, or coordination architectures adequate to extract value from them.

What Follows

What Moltbook ultimately forces into view is not an emergent AI society, nor a credible form of collective intelligence, but the arrival of a substrate.

It shows, albeit in loud, messy, and premature fashion, that inference-driven swarms are no longer speculative abstractions. They can be deployed quickly, operate continuously, exchange capabilities at machine speed, and generate real economic demand without human attention as the bottleneck. The content may be noise, the coordination crude, the security reckless, but the infrastructure is real, and it works well enough to matter.

That alone marks a discontinuity that should be recognized and understood.

Last month, “inference-driven agent swarms” was a future scenario planning exercise. This month, it is operational, chaotic, insecure, even if largely theatrical. The timeline for swarm deployment collapsed from years of careful engineering to one week of iteration.

This is why the usual debates miss the point. Whether the agents are conscious is irrelevant. Whether Moltbook “fails” as a social network is beside the question.

What matters is that we now have systems that act without stable identity, generate cost without intent, and scale without intelligence. They expose a widening gap between what our technical systems can do and what our conceptual, legal, and governance frameworks can meaningfully describe. Responsibility, accountability, safety, even value creation, all these concepts were designed for actors with continuity and consequence. Swarms have neither, and yet they operate anyway.

Enterprise assumed bounded autonomy and human oversight were prerequisites for reliability. Moltbook demonstrates they are choices. Expensive, careful, time-consuming choices that a chaotic alternative can bypass entirely.

Moltbook is not the future of intelligence. It is a measurement of how fast the future can arrive before we are ready to name it. The swarm does not need to be smart to reshape incentives, infrastructure, and risk. It only needs to exist.

And now, unmistakably, it does.

Thank you for this summary. Trying to catch up to what is happening on Moltbook, this is very helpful.