The $285 Billion 'SaaSpocalypse' Is the Wrong Panic

AI labs aren’t winning by intelligence alone, SaaS isn’t dying, and the real battle is over who becomes the system of action in the agentic enterprise. That battle is a symetric one.

Last week’s $285B “SaaSpocalypse” selloff, sparked by Anthropic’s Claude Cowork plugins, lumps all software stocks together, slashing terminal values as if AI labs have already won. Workflow wrappers and thin AI apps face existential commoditization as labs move up the stack. But systems of record like Salesforce, ServiceNow, and Workday confront a winnable transition: evolving into “systems of action” that orchestrate agents via irreplaceable context and proximity to user intent. Incumbents are advancing toward this paradigm while simultaneously building the API-mediated agent layer. The market prices this probability at zero, ignoring labs’ own commoditization risks and the symmetric race from opposite stack ends, creating a massive mispricing opportunity.

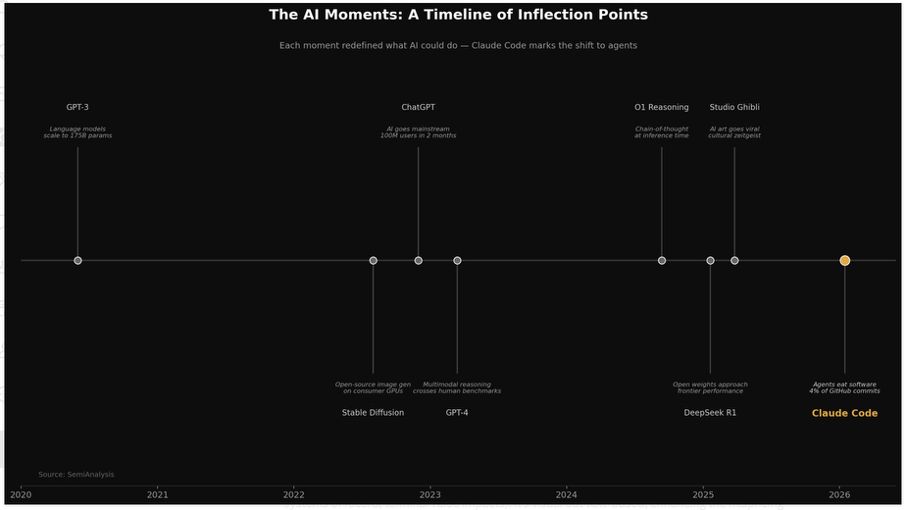

AI has entered another period of acceleration, and markets are once again flailing without a coherent framework.

I have been decoding the latest steps of this acceleration phase through Claude Code, then Claude Cowork, then OpenClaude, and then Moltbook. At the end of January, Anthropic then dropped plugins, a way to extend Claude Cowork's functionality by automating specialized tasks within an enterprise department.

One of the 11 plugins was a legal plugin, a domain-specific extension that automates contract review, NDA triage, and compliance workflows for in-house legal teams. It is, by any honest assessment, a relatively modest feature drop: an open-source plugin on GitHub, built in a matter of weeks.

The market’s response was anything but modest.

In 48 hours, $285 billion in market capitalization evaporated from global software and services stocks. Thomson Reuters fell 16%. RELX dropped 13%. CS Disco sank 12%, and LegalZoom plummeted 20%. A Goldman Sachs basket of U.S. software stocks recorded its largest single-day decline since the tariff-driven selloff of April 2025. Jefferies’ equity trading desk coined a term for the carnage: the “SaaSpocalypse.”

Two days later, Anthropic released Claude Opus 4.6, its most advanced model to date, featuring a one-million-token context window, record-breaking agentic coding benchmarks, and a new “agent teams” capability allowing multiple AI agents to coordinate on complex projects in parallel. Opus 4.6 launched with a direct PowerPoint integration, a pointed challenge to Microsoft’s Copilot. This arrived 72 hours after OpenAI launched a desktop application for its Codex AI coding system, designed to transform software development into something akin to managing a fleet of autonomous developers.

And so, over the span of five days, the cumulative effect of these announcements shocked the markets into reluctantly recognizing that the AI labs are no longer just building larger frontier models and then selling APIs to software companies. They are moving up the food chain and coming after the software companies’ markets.

Unfortunately, while the market’s reaction may have been directionally correct for some categories, it has been analytically lazy.

The undifferentiated selloff treated Thomson Reuters, ServiceNow, Salesforce, and LegalZoom as though they faced the same threat. They do not. The SaaSpocalypse narrative conflates two very different questions, and collapsing them into a single panic trade has created both severe mispricing and a genuine analytical blind spot.

This is not the first time we have seen this since the start of the generative and agentic AI discontinuity, and it surely won’t be the last. But it is critical to understand that this is a confused, simplistic attempt to price a structural shift in where control, coordination, and value capture will live as autonomous agents become the primary actors inside enterprises.

This recent market panic is mispricing reality by collapsing fundamentally different business models into a single narrative. And, in doing so, missing where the next generation of durable enterprise power will actually reside.

The real question is not whether AI replaces software, but which layer of the stack becomes the locus of intent, decision-making, and execution, and which layers are reduced to interchangeable utilities. Once you understand those elements, you can begin to make a much more informed analysis of which companies are vulnerable, perhaps even doomed, and which face threats but also have a genuine opportunity for transformation and leadership into the Agentic Era. And this does not just apply to enterprise software. It applies to four of the AI IPO contenders of 2026, who are in that same stack: OpenAI, Anthropic, SpaceX (with the merger with xAI), and Databricks.

We can start by asking two fundamental questions:

Is your software a system of record or a workflow wrapper?

If you are a system of record, can you become the system of action, the layer that tells AI agents what to do, and not just the database they query?

The answers separate the companies facing existential risk from those facing a value capture negotiation. Confusing the two is the most expensive analytical error in today’s market.

Lurking behind both questions is a structural argument about the AI labs themselves that almost no one is making, one that complicates the SaaSpocalypse narrative far more than the market has begun to price. The unpriced reality is that AI labs are moving up the stack not from strength but from necessity, because the model layer is commoditizing faster than enterprises can be rewired. These players recognize that orchestration, not intelligence, is the real control point. Yet there is plenty of evidence that any edge they have in model power will not automatically give them an advantage at the orchestration layer.

The coding wedge: How AI labs enter the enterprise

To understand the events of this week, you need to understand the mechanism by which AI labs penetrate enterprise workflows, what I have called the “coding wedge.”

Software engineering is where autonomous agents first crossed the reliability threshold for production deployment. Amid the debates about ROI and the effectiveness of these various tools, coding has emerged as the killer app, the spreadsheet of the LLM age.

The coding wedge is the strategic entry point through which AI systems learn orchestration under conditions of certainty, embedding themselves into enterprise workflows by mastering the one domain where outcomes are verifiable, dependencies compound, and feedback loops are irreversible. By shaping code, AI does not just automate a task; it establishes orchestration loops that create behavioral lock-in, propagate across organizations, and make switching technically easy but operationally prohibitive.

Because Claude Code gained an early performance edge over ChatGPT in coding, it leveraged that into a larger enterprise market share. OpenAI has been trying to catch up ever since.

OpenAI’s framing of Codex is revealing: “Everything is controlled by code. The better an agent is at reasoning about and producing code, the more capable it becomes across all forms of technical and knowledge work.” They are not being coy about the strategy. Building the best coding agent, in their own words, “has also laid the foundation for it to become a strong agent for a broad range of knowledge work tasks that extend beyond writing code.”

Code is not the destination. It is the training ground for general enterprise orchestration.

Meanwhile, Claude Code achieved $1 billion in run-rate revenue within six months of launch. The company’s enterprise market share surged from roughly 10-15% to 32%, not because Claude’s benchmarks were marginally better, but because Anthropic built an agent-first ecosystem. Model Context Protocol became the industry’s universal connector, adopted even by competitors. Developers chose Claude, and in doing so, embedded specific orchestration patterns that became organizational muscle memory.

And as I noted above, then came Cowork, extending agentic capabilities to non-developers. Then came the plugins, including legal, sales, finance, and marketing.

Code was the wedge Anthropic used to open the enterprise door. Plugins are how it’s walking through and going further and further inside

What spooked the market was the realization that this path works, and that it works fast. Anthropic didn’t need years of enterprise sales cycles to threaten Thomson Reuters. It needed a plugin built over the course of weeks by its own coding agent. The success of Claude Code has begun to compound.

The speed itself is now the disruption.

But to respond intelligently to this kind of acceleration, the markets’ analysis must be more precise rather than more general. Let’s look more closely at the major categories to better understand how to think about the frameworks that can guide us.

The real casualties

The greatest carnage from this week’s events will be the venture-funded wave of AI application companies built between 2023 and 2025: legal AI startups, AI-powered analytics platforms, AI writing assistants, and AI sales tools.

These companies raised hundreds of millions collectively on a thesis that there would be a durable margin between what a foundation model could do and what an enterprise needed done, and that this margin would support an independent application business. That now looks flawed.

What Anthropic demonstrated this week, and what OpenAI’s Codex desktop app confirmed, is that the foundation model providers have no intention of respecting that moat. This is just as many of the founders of companies, such as Harvey have been expecting. Last fall, Harvey co-founder Winston Weinberg said in an interview that he considered OpenAI its largest potential competitor, even though OpenAI had invested in Harvey through a startup program. While Harvey has raised $300 million and built a solid client base in the legal sector, it faces the prospect of Anthropic offering many of the same specialized interfaces and tools. Will Harvey’s early traction in the legal sector and its singular focus on the market be a difference maker for clients in that sector? It has to hope so because, from a technical perspective, a legal AI startup built on OpenAI and Claude’s API has a limited data moat and minimal switching costs.

The second category is the public-market equivalent, which could be described as “workflow wrappers.” These are established SaaS companies that bundle general-purpose functions - like writing, analyzing, reviewing, or routing - with a user interface, some integrations, and a subscription model. They typically don’t hold unique data or serve as the core of an enterprise’s operational systems. LegalZoom’s 20% drop reflected market concerns that it focuses on standard legal workflows without proprietary data edges that might not withstand AI replication.

The common vulnerability is identical: if your product is “model + wrapper + workflow” and the model creator can cut out the middle, the moat was never structural. It was temporal. You were arbitraging a gap that is now closing at the speed of a plugin deployment.

Palantir CEO Alex Karp said as much on his earnings call last Monday, the catalyst that primed the market for Tuesday’s explosion: AI is now so good at writing and managing enterprise software that many SaaS companies risk becoming irrelevant.

For workflow wrappers and thin AI apps alike, this argument is sound.

The system of record: Different question, different stakes

However, if you are a system of record, then the story is very different.

Salesforce is not LegalZoom. ServiceNow is not CS Disco. Workday is not a legal AI startup that built a wrapper around Claude’s API.

These companies are systems of record. They hold the canonical data that enterprises operate on. Salesforce owns the customer graph across sales, service, and marketing. ServiceNow owns the operational workflow layer, including IT service management, HR service delivery, and security operations. Workday owns the employee lifecycle, including payroll, benefits, workforce planning, and financial management. SAP and Oracle own the ERP backbone, including supply chain, manufacturing, procurement, and financial consolidation.

Ripping these out isn’t about switching to a cheaper plugin. It means migrating decades of operational data, retraining thousands of users, rebuilding integrations with dozens of downstream systems, and accepting the risk of operational disruption in mission-critical processes. Nobody is building a homegrown CRM in Replit to replace their Salesforce instance.

The market, in its panic, has forgotten this.

But systems of record face a different threat, one that is more subtle, and arguably more consequential for long-term value capture. The question is not whether the system of record survives. It’s whether the system of record captures value like a platform or gets priced like a database.

This is the distinction between being the system of action and being the system of storage.

In the pre-agentic world, the system of record was also the system of action. When a sales rep wanted to update a deal, they opened Salesforce. When an IT manager needed to route a ticket, they opened ServiceNow. The application was the interface where intent met execution. That’s where the user lived, and that’s where the value accrued.

In the agentic world, intent no longer starts in the application. It starts in a conversation.

A user tells an AI agent: “Update the pipeline forecast for Q2.” The agent calls into Salesforce’s API, reads the data, performs the analysis, and reports back. This all happens without the user ever opening Salesforce’s interface. Salesforce is still essential. But it risks being relegated from the system of action to the system of storage, just the database behind the LLM.

Systems of record are not dying. But their economic role in the stack is being renegotiated. The outcome determines whether these companies trade at 5x revenue (or less these days) or 25x revenue, a difference of hundreds of billions in market capitalization.

This brings us to the question the market should actually be asking: not whether the systems of record survive, but whether they can make the transition from system of storage to system of action.

To understand the answer, you need to see where the technology is today and where it is going.

Where we are today: The API era

Right now, we are in the early innings of the agentic transition, and the interface between AI agents and enterprise software is structured and mediated.

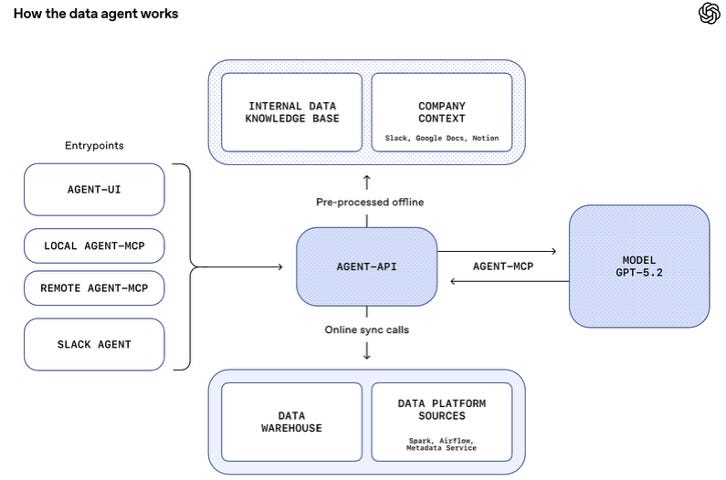

Agents interact with systems of record primarily through APIs and protocols. This is the world of Agentforce, ServiceNow’s workflow APIs, and MCP server integrations. These are structured endpoints that expose enterprise data and functionality to AI agents in controlled, permissioned ways. UC Berkeley’s recent MAP study shows 92%+ of deployed agents serve human users through controlled interfaces, and research documents MCP, A2A, HTTP/REST as the current mediation layer.

In this phase, the system of record retains significant structural leverage. It controls which data the agent can access, which actions the agent can take, and which workflows the agent can trigger. The API is a gate, and the incumbent holds the key. This is why Salesforce’s integration of MCP into Agentforce matters: it positions Salesforce as the mediation layer between AI agents and customer data. It is why Benioff’s framing of managing “human and digital workers” on the same platform is not merely marketing, but an architectural claim about control.

The early evidence is encouraging for incumbents who are moving. Salesforce is positioning Slack as the intent gateway, the conversational surface where employees express goals that get routed through Salesforce’s orchestration layer. The Agentforce Command Center provides a unified view of agent activities; persistent memory ensures agents retain context across interactions. ServiceNow is making the analogous move with its workflow engine.

Both companies are attempting to become the orchestration layer - the system of action - rather than passively waiting to be queried.

But this API-mediated phase is transitional. It will not last. And what comes next significantly changes the competitive dynamics.

Where we are going: From a system of storage to action

A new category of “Large Action Models” (LAMs) is emerging, pointing toward the next phase of the agentic transition. And it is radical.

Through LAMs, agents operate enterprise software through the user interface itself exactly as a human would. This swarm of agents reason, click, type, and navigate. These UI agents are pretrained to be able to operate specific classes of enterprise tools such as ERP systems, CRM platforms, revenue cycle management, and IT service management. They aim to work through HTML, native desktop applications, and even virtual desktop environments where no back-end API exists. They self-heal when interfaces change. Nothing is (or at least should be) hard-coded. Claudius, while not purely a UI agent, demonstrated action-taking beyond APIs and paved the way for this transition.

The emergence of UI agents has two profound implications for the system-of-record question.

The first is that the API gateway, the structural leverage that incumbents currently enjoy, will erode. When an AI agent can operate any application by simply using its interface, it no longer needs the incumbent’s permission or the incumbent’s MCP integration. It just opens the application and works. This accelerates the urgency for systems of record to complete the transition to systems of action, because the API-era leverage they currently enjoy is a wasting asset.

The second implication is more consequential, and it cuts in the opposite direction.

A UI agent, no matter how sophisticated, needs to know what to do, not just how to click. The agent needs to know which approval path to take for this specific deal, which escalation logic applies to this class of incident, and which exceptions are routine and which require human review. That orchestration logic is the accumulated context of how an enterprise actually operates.

This is precisely what a system of action provides. And it’s where the transition from a system of storage to a system of action becomes the decisive question.

A system of record that remains passive storage, a database the UI agent queries for a number, will indeed be devalued, its leverage eroded by agents that can bypass the API and navigate the interface directly. But a system of record that has become a system of action, that is close to the user intent, that owns the orchestration logic, the decision trees, and the contextual understanding of this company’s specific processes, becomes the brain that tells the UI agent what to do.

The agent is the hands. The system of action is the brain.

In the UI agent era, the interface is commoditized. The model is commoditized. The only durable moat is the orchestration context that makes the agent’s actions correct rather than merely fast.

The possibility that the market is ignoring

This is the core analytical failure of the SaaSpocalypse trade.

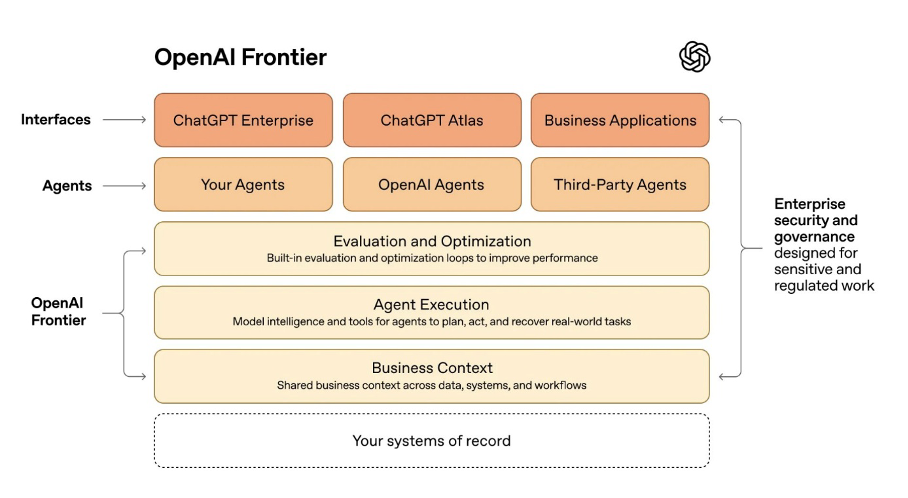

The market is pricing the systems of record as though the only possible outcome is demotion to a system of storage, as though the AI labs will inevitably own the orchestration layer and the incumbents will inevitably become passive databases behind the LLM. This is largely relayed by the AI labs themselves, starting with OpenAI.

The possibility that systems of record can make the transition to systems of action, and that doing so would make them more valuable in the agentic era, not less, is being discounted to near zero.

That discount is not justified by the evidence.

Consider what the systems of record actually possess. Salesforce doesn’t just store customer records. It encodes which sales processes actually close deals for a specific company, which stakeholders need to be looped in, and which exceptions are routine and which are genuine red flags. ServiceNow doesn’t just track tickets. It understands the operational topology of an enterprise’s IT estate, the escalation paths, and the SLA hierarchies.

This contextual depth accumulates over years of deployment, customization, and operational learning. It is the difference between an AI agent that can generically “update a pipeline forecast,” and one that knows this company’s pipeline requires sign-off from regional VPs, uses a non-standard stage progression, and has historically overweighted Q4 deals by 15%.

An AI lab cannot replicate this context with a plugin. It can replicate within weeks the capability, such as the ability to read contracts, write analyses, and generate reports. But capability without context produces generic outputs. Context is what makes agentic orchestration enterprise-grade.

If a system of record successfully becomes a system of action, every new AI interface, whether it’s achatbot, UI agent, coding agent, or voice assistant, becomes a channel that routes through its orchestration layer, drawing on its context to determine what should happen next, powered by whichever model and whichever agent is best suited to each task. In that architecture, the system of action grows more valuable as agents proliferate, not less.

Can every system of record make this transition? No. The window is measured in quarters, not years. Not all incumbents will move fast enough, and not all have the architectural foundation to support it. But the possibility is real. The evidence of early execution exists.

And yet, the market is pricing it at approximately zero.

The LLM lock-in paradox

Now, let’s have the analysis take an unexpected turn. And it should further unsettle anyone treating the AI labs as the unambiguous winners of the SaaSpocalypse.

The market’s panic was predicated on a simple theory: LLMs are eating SaaS, therefore LLM providers win, and SaaS incumbents lose. But this contains a hidden assumption that does not survive contact with how enterprises actually deploy AI.

The assumption is that the LLM itself is the durable control point. It is not.

Menlo Ventures’ mid-year 2025 data revealed the paradox: Despite model performance convergence and unprecedented ease of technical substitution, only 11% of enterprise builders switched AI providers in the previous year. As I wrote in the “11% Paradox,” orchestration lock-in was being caused by the organizational complexity of recalibrating prompts, validating tool interactions, and ensuring behavioral consistency. But the corollary is equally telling: the reason for switching is technically trivial is that the model layer is architecturally the most substitutable component in the entire stack.

Enterprise AI architectures are converging on compound systems that orchestrate multiple models, multiple tools, and multiple data sources into coordinated pipelines. The model-agnostic platform approach is gaining traction in both research and enterprise practice because it treats the LLM as one module among many. The UI agent action layers already operating in production route each step to whichever foundation model, proprietary or open-source, best fits the task. The LLM is a replaceable cog in a larger machine.

Ask yourself: which lock-in would an enterprise CFO prefer: Being locked into a CRM that holds 15 years of customer data, process customizations, and institutional context that would take two years and $50 million to migrate? Or, being locked into a foundation model that could be swapped for a competitor by changing an API endpoint?

CRM lock-in is deep, structural, and data-driven. LLM lock-in is behavioral and organizational. That is real, but fundamentally more fragile. An enterprise can retune prompts in weeks. It cannot rebuild its customer data or HR graph in that timeframe.

This means the LLMs face their own strategic imperative that the SaaSpocalypse narrative ignores entirely: they need to move upstream in the enterprise to build durable moats beyond the model layer. This is exactly what Anthropic is doing with MCP, Cowork, and the plugin ecosystem. It is attempting to become the orchestration substrate, not just the intelligence engine. It is what OpenAI is doing by acquiring Windsurf and building Codex into a fleet management tool for developers. They are racing to create the same kind of workflow entrenchment that Salesforce and ServiceNow already possess.

The irony should not be lost. The LLMs are trying to become enterprise platforms with deep organizational lock-in. In other words, the very things they appear to threaten. They need to accumulate context, build workflow integration, and create switching costs that go beyond their models. To do that, they need to become systems of action themselves. They are running in the same race and towards the same finish line as the incumbents, just from the opposite direction.

The AI labs have speed and capability. The incumbents have context and data gravity. The architectural evidence, such as compound AI, model-agnostic action layers, and UI agents that treat models as interchangeable, suggests that context, not capability, is the scarcer resource. Capabilities improve on a curve measured in months. Context accumulates on a curve measured in years.

What the market should actually be pricing

The SaaSpocalypse is a repricing event, not an extinction event. But it is repricing the wrong companies in the wrong proportions. Let’s remember that in software, the terminal value constitutes the bulk of the stock price, driven by perpetual growth assumptions.

For workflow wrappers/AI apps as per above, the market is rightly cutting terminal value here - e.g., stock drops reflect a path to zero margins as plugins commoditize wrappers, eroding perpetual revenue streams.

But for Salesforce/ServiceNow/Workday/SAP/etc., i.e., the systems of record, the pricing assumes terminal demotion to storage, and ignores the upside if they win orchestration. If they transition, terminal growth could accelerate (with unpriced network effects from agent proliferation, absent in the SaaS 2.0 paradigm), justifying much higher multiples. The zero-probability discount creates a mispricing opportunity.

The wedge isn’t a moat

What last week revealed is not a software apocalypse, but a control transition.

The agentic era is not destroying enterprise systems; it is re-ranking them based on where intent originates and how execution is coordinated. Coding is the wedge. It gets AI labs through the enterprise door. But a wedge is not a moat.

Products that exist to mediate human clicks are being hollowed out. Systems that encode organizational memory, decision logic, and operational context are being forced to choose: remain passive infrastructure or become the brain that directs increasingly autonomous work.

This is a clarifying event that exposes which positions in the technology stack are structurally defensible and which were living on borrowed time.

This is why the market’s reaction is so imprecise. It is collapsing a race that is still very much underway into a single outcome that has not yet occurred. AI labs are not the inevitable owners of enterprise orchestration; they are late entrants attempting to climb from intelligence into control before model commoditization erodes their leverage. Systems of record are not doomed incumbents; they are context-rich platforms facing a narrow window to reassert themselves as systems of action.

Both sides are running toward the same prize from opposite ends of the stack - and neither has won it yet.

The AI application startups and workflow wrappers are the genuine casualties, caught between a model layer moving up and a future in which any interface-only product can be bypassed.

The real discontinuity is not who builds the best model, or even who builds the best agent. It is who owns the accumulated understanding of how work actually gets done. That means things like which exceptions matter, which approvals are real, and which actions are safe to automate.

In a world where agents can click any interface and models can be swapped like APIs, that context becomes the only defensible moat.

The wedge has already done its job. What remains is the harder question: who turns orchestration into ownership.

This analysis builds on my previous work on the coding wedge, orchestration economics, and the laws of value in the Agentic Era: The Coding Wedge · Orchestration and Asymmetric Returns · The 11% Paradox · First Law of Value · Second Law of Value