Decoding Anthropic’s $380 Billion Valuation: Orchestration over Raw Intelligence in Enterprise AI

How AI Labs are pivoting from models to platforms, and what It means for the Enterprise AI race.

Last week, I examined the enterprise technology structural shift in “The $285 Billion SaaSpocalypse Is the Wrong Panic.” I argued that SaaS incumbents are more resilient than the market assumes because they hold the context and workflow authority required by AI orchestration. This piece is the counterpart: the same structural shift, examined from the attackers’ side. What are the AI labs building, and what justifies a $380 billion valuation?

AI labs like Anthropic and OpenAI are shifting focus from commoditizing models to orchestration platforms that coordinate agents, workflows, and enterprise context, justifying sky-high valuations like Anthropic’s $380B. OpenAI’s Frontier bets on a horizontal control plane for interchangeable agents, while Anthropic’s Cowork emphasizes vertical integration for deep embedding and switching costs. Success hinges on outpacing model commoditization, building context faster than incumbents, and navigating massive burn rates, with risks like open-source erosion and compute traps threatening the transition.

The LLM battlefield has shifted. To understand the new frontline, consider the latest volley exchanged this month between the “Great Model Powers.”

OpenAI began the month by releasing GPT‑5.3‑Codex, the most powerful update to its coding model since GPT-5 was released last August. This represented a critical moment for the company as it sought to regain ground in the critical fight for the “coding wedge.”

As I wrote at the release of GPT-5, the “coding wedge” has become the strategic beachhead, where winning developers in coding workflows provides the leverage to win enterprise AI adoption and broader orchestration control. Even back then, coding had emerged as the first domain in which autonomous agents were reliable enough for real production use, becoming a practical proving ground for capability and cost.

For much of last year, I preached that whoever controls how developers build with AI gains control of the orchestration layer, which then extends from developers to all knowledge workers and enterprise workflows.

At the time, conventional wisdom portrayed OpenAI as an unstoppable juggernaut. But if you understood the coding wedge, then you weren’t surprised as Anthropic seemed to surge last fall in terms of both enterprise and mindshare. Since the start of 2026, Anthropic has appeared to be transforming from an OpenAI also-ran into a cultural phenomenon, thanks to Claude Code, its developer tool, launched barely a year ago. Following the release of the latest Claude model in November, developers began flocking to Claude, singing its praises, generating buzzy headlines in the Wall Street Journal, gushing over the release of Claude Cowork for mainstream users, and then the viral success of OpenClaw, the open-source framework created by Austrian developer Peter Steinberger that runs on any LLM but was clearly optimized for Claude (thus the original name: Clawdbot).

Originally called Clawdbot, then Moltbot after Anthropic requested a trademark change, OpenClaw allows users to deploy autonomous AI assistants on their own hardware. And that, in turn, spawned the media sensation of Moltbook, a Reddit-like platform where agents could congregate, and humans could gawk at the machine interactions.

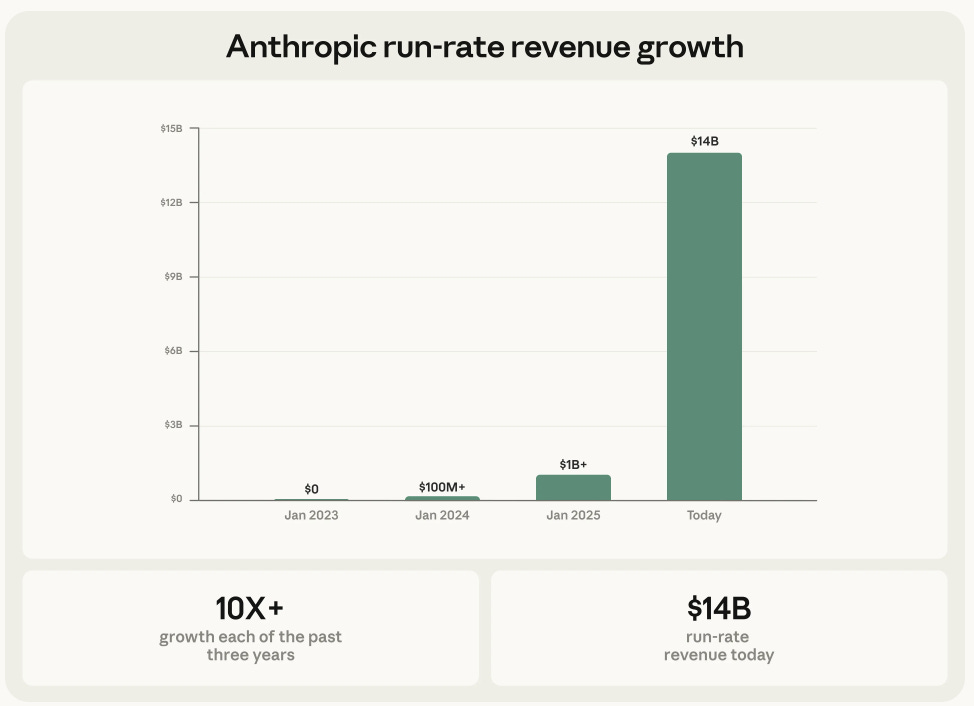

Anthropic’s shadow suddenly loomed so large that the announcement of plugins for verticals such as legaltech for its Cowork platform, ultimately still a niche product, triggered the $285 million SaaSpocalypse on Wall Street. An event that managed to almost completely drown out OpenAI’s Codex launch news that came the same day. Beyond the hype, Claude Code is generating $2.5 billion in ARR, a significant portion of Anthropic’s $14 billion ARR, which has grown more than tenfold annually over the past three years.

But Claude Code is not just a peripheral product. It is the very core of what has propelled Anthropic to this position. It’s why Anthropic closed a $30 billion funding round at a valuation of $380 billion, more than double its $183 billion valuation from just five months earlier, and the second-largest private funding round in technology history.

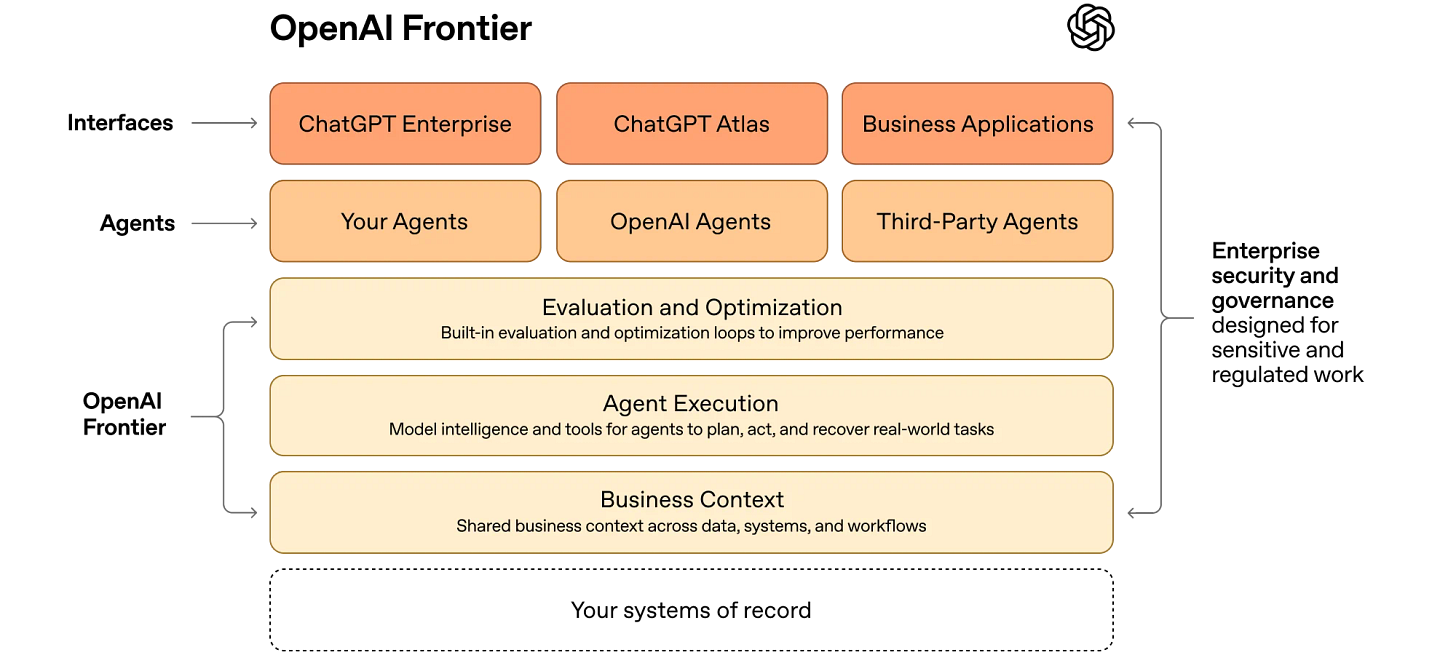

OpenAI understands this. It’s why the company spent half of its August GPT-5 launch talking about coding. And it’s why, as part of the latest Codex release on February 5, it did something that received less attention than it deserved. The company launched a product called Frontier. Not a new model, not an upgrade to GPT, but an enterprise platform for deploying and managing AI agents across business systems.

Agents on Frontier receive employee-like identities with scoped permissions. They connect to data warehouses, CRM systems, and internal applications through what OpenAI calls a “semantic layer for the enterprise.” They build institutional memory from their interactions over time.

The most critical thing to know is that they do not need to be OpenAI’s agents. Frontier manages agents from Anthropic and Google. Fidji Simo, OpenAI’s CEO of Applications, proclaimed: “We’re not going to build everything ourselves. We are going to be working with the ecosystem.”

Then, last weekend, OpenAI staged a minor coup by announcing the hiring of Steinberger, the man behind OpenClaw, “to drive the next generation of personal agents,” according to CEO Sam Altman. “We expect this will quickly become core to our product offerings. OpenClaw will live in a foundation as an open-source project that OpenAI will continue to support.”

On the surface, it would be easy to conclude that the AI labs are once again sucking up all of the oxygen, resources, and talent.

But take a closer look to find the real meaning behind these announcements.

The AI labs are leaving the model layer behind. The labs are building platform companies.

The fight is now for the orchestration layer.

They are not completely abandoning models. These remain the substrate on which everything else is built. But look at what these companies are actually building. Not what they say, but what they ship, and the picture becomes clear.

Every significant product that OpenAI and Anthropic have shipped in the past six months reveals that neither company believes the model layer alone can sustain these valuations. Claude Code, Cowork, the vertical plugins, Frontier, and Codex are not model improvements. All of them are orchestration infrastructure: systems designed to coordinate AI agents across enterprise workflows, accumulate institutional context, and create the switching costs that justify platform multiples.

Consider that $380 billion valuation. At $14 billion ARR, that represents a 27x multiple. If Anthropic is a model company selling intelligence in a market where intelligence is converging, then this is an extraordinarily aggressive bet on a commoditized asset. As I noted in May 2025, benchmark scores were already converging by 5%. Open-source alternatives have narrowed the gap between commercial leaders, as I cited in my analysis of MiniMax’s IPO, a Chinese lab with a fraction of the capital intensity of US peers. But if Anthropic is a platform company, selling orchestration, workflow coordination, and accumulated enterprise context, then 27x may be the entry price for a generational enterprise franchise.

The distinction between these two readings is the difference between fragile and durable.

Victory is hardly inevitable. In the SaaSpocalypse article, I explored the nuances required to understand which incumbents are vulnerable and which have the potential to transform themselves for the Agentic Era.

As for the AI labs making a play to become platform players, last week I wrote:

“The unpriced reality is that AI labs are moving up the stack not from strength but from necessity, because the model layer is commoditizing faster than enterprises can be rewired. These players recognize that orchestration, not intelligence, is the real control point. Yet there is plenty of evidence that any edge they have in model power will not automatically give them an advantage at the orchestration layer.”

With OpenAI and Anthropic expected to go public sometime this year, I want to dive deeper into that question, particularly. The new paradigm of Orchestration Economics is just beginning to take shape, and it will require investors to develop new tools and frameworks to price the valuations and risks in the Agentic Era.

What orchestration means

The term “orchestration” is used loosely in the industry. Its specificity matters for valuation. So, it is worth defining precisely.

Orchestration in the enterprise AI context is the set of systems that enable AI agents to perform useful work within organizations. This includes:

Connection protocols that link models to enterprise data and applications.

Agent frameworks that guide multi-step reasoning across complex workflows.

Governance systems that ensure compliance, auditability, and appropriate permissions.

Accumulated context, the institutional memory, that allows an AI system to understand not just what a task requires in the abstract, but how this organization, with its processes and exceptions and approval chains, gets work done.

Model intelligence answers the question: Can the AI do this task?

Orchestration answers the question: Can the AI do this task, here, within this organization’s systems, rules, and workflows, reliably enough that the organization will depend on it?

Orchestration is a strategic position in the Agentic AI era, one that enables you to capture user intent and turn it into a business outcome by commanding these systems.

This is the difference between a technology and a business. I believe this is the most important distinction in enterprise technology today, one that I first developed in my analytical work on the Agentic Era, and subsequently pressure-tested during a private due diligence engagement evaluating Anthropic’s competitive positioning when the company was valued at approximately $170 billion.

In that assessment, I identified three moat pathways:

enterprise orchestration

coding dominance

vertical specialization

I concluded that the orchestration thesis was “achievable but unproven.”

Nine months later, the thesis has moved from analytical to operational. It is no longer a prediction about where the labs might go. They have arrived.

Two architectures, two bets

The two leading AI labs have arrived at the orchestration layer with structurally different visions. Both have real products, launched within weeks of each other, that embody different assumptions about how the enterprise AI market will evolve.

Understanding the divergence is essential for valuing the companies

Frontier is a control plane

OpenAI’s architecture positions Frontier as the management layer that sits above all agents, its own and everyone else’s. Each agent receives an identity with explicit permissions, governance boundaries, and audit trails. The platform connects to enterprise systems through standardized integrations and accumulates institutional memory from agent interactions over time.

The design choices reveal the strategic intent. Frontier’s agent identity management mirrors human HR systems: onboarding, scoped permissions, and performance monitoring. OpenAI is not being metaphorical when it describes agents as “digital coworkers.” It is making an architectural claim. If AI agents operate as enterprise employees, the platform that manages them becomes as essential as the system that manages human employees. Frontier aspires to become the Workday for AI labor.

The critical decision is openness. Frontier accepts agents from any provider.

This appears generous. In fact, the strategic calculus is precise.

By welcoming competitors’ agents onto its platform, OpenAI concedes agent-layer competition in exchange for control-plane dominance. If enterprises standardize on Frontier for agent governance, OpenAI captures the value of orchestration regardless of which model powers any individual agent.

The agents become interchangeable components. The control plane does not.

This is horizontal platform logic. AWS applied to enterprise AI. It does not require OpenAI to have the best model. It requires OpenAI to have the best coordination infrastructure.

Cowork is an agent that became a platform

Anthropic’s architecture follows a different logic. Rather than building a management layer on top of agents, Anthropic has built outward from the agent itself. The sequence is methodical and each step compounds on the last. Claude Code proved the model could execute complex, multi-step enterprise tasks in the high-stakes domain of software engineering. It generated $2.5 billion in revenue. MCP, Anthropic’s Model Context Protocol, standardized how agents connect to external systems and was adopted by competitors, including OpenAI and Google, establishing it as an emerging industry standard. Cowork is extending orchestration beyond developers to knowledge workers. The vertical plugins, such as legal, financial analysis, sales, and marketing, created purpose-built entry points into specific business functions.

The strategic logic is vertical integration. Anthropic is betting that agent quality remains meaningfully differentiated when embedded within orchestration. In that framing, the experience of using Claude to coordinate a complex legal review or financial analysis is sufficiently superior so that enterprises will build their workflows around it. This is closer to Apple’s logic: control the end-to-end experience, build an ecosystem around your product, and make execution quality the moat.

But there is a subtle departure from the Apple analogy. MCP is open-source. Anyone can implement it. This appears to undermine lock-in.

The answer lies in what I observed in my work on enterprise AI adoption: only 11% of enterprise builders switched AI providers, even though technical substitution was trivial. The lock-in is not technical. It is organizational.

When an enterprise builds workflows around Claude’s specific orchestration patterns, the cost of switching becomes operational. By that, I mean Claude’s approach to multi-step reasoning, its tool-use conventions, and its plugin interfaces. You can swap the model in an afternoon. You cannot retune thousands of enterprise workflows in an afternoon.

Anthropic is making a layered bet: MCP creates ecosystem breadth (every system connects), Claude’s quality creates ecosystem depth (Claude is preferred within that ecosystem), and organizational adoption creates inertia (no one switches even when they could).

A market phenomenon of behavioral lock-in despite technical substitutability becomes a deliberate business strategy.

The two architectures represent different bets about the speed and completeness of model commoditization.

If intelligence commoditizes fully, Frontier wins. The platform that coordinates interchangeable agents captures the greatest economic value. OpenAI wins not because GPT is superior, but because Frontier is the control plane. It wins even if Claude is the better agent, because the control plane sits above the agent layer.

If intelligence retains meaningful differentiation when embedded in orchestration, Cowork wins. Enterprises do not want “any agent, well-managed.” They want the best agent, deeply embedded. And the switching costs compound with every workflow built around it.

There is a third possibility that neither lab discusses, but that investors must take seriously. I examined this in the SaaSpocalypse: The incumbents build their own orchestration layers around the enterprise context they already possess. Salesforce with Agentforce, ServiceNow with its AI orchestration capabilities, and Workday with its emerging agent infrastructure.

In this scenario, the labs become what they are most afraid of becoming: model providers that orchestration platforms call upon. Sophisticated tools, but just tools nonetheless.

The three scenarios are not mutually exclusive. Different industries, workflow complexities, and regulatory environments may favor different architectures. The most consequential analytical work for investors over the next two years will be determining which architecture dominates in which enterprise contexts and pricing the outcomes accordingly.

Justifying $380 billion

If orchestration, not intelligence, is what drives the labs’ valuations, three conditions must hold. I identified these conditions during my earlier analytical work on Anthropic and have tracked them since.

Orchestration lock-in must prove durable, not merely behavioral. Enterprises are not switching AI providers today. But this was measured during a period of rapid growth when no one had reason to test the limits of their commitment. The real test arrives when Frontier offers agent-agnostic orchestration at compelling economics, or when a competitor undercuts on price. MCP is open-source. It creates connectivity but not captivity. For $380 billion to be justified, the network effects must become self-reinforcing: more workflows generate richer context, produce better orchestration, and attract more workflows. This flywheel is architecturally plausible. It is not yet empirically confirmed at scale.

The coding wedge must compound. Claude Code’s $2.5 billion ARR validates the entry strategy, the mechanism by which the labs first penetrated enterprise workflows through software development. But the path from coding to legal, finance, HR, and general operations is the critical progression. If the vertical plugins drive cross-functional adoption, the platform thesis holds. If coding remains the dominant revenue line while other verticals grow incrementally, Anthropic is a remarkable single-function business at enormous scale. That is a different valuation than an enterprise platform.

The labs must accumulate enterprise context faster than incumbents can defend. This is the argument from the SaaSpocalypse, now examined from the opposite side. I argued there that systems of record are resilient because they hold decades of accumulated institutional context: the workflow knowledge, compliance history, and operational understanding that orchestration depends upon.

The labs are starting from zero. Frontier builds “institutional memory” from agent interactions. That memory is weeks old. The institutional memory embedded in a Fortune 500 company’s Salesforce deployment spans years.

The labs have speed and adaptability. The incumbents have depth and irreplaceability. The labs must build enterprise context before model commoditization erodes the intelligence advantage that gives them the right to orchestrate.

This is a race against the clock. The clock does not pause for fundraising announcements.

The cost of becoming what they need to become

There is a dimension of this transformation that the market has yet to price: the expense of becoming an enterprise software company.

The market narrative portrays AI labs as asset-light technology companies that are disrupting bloated incumbents. The reality is more complex.

To win the orchestration layer, the labs must build what every enterprise platform company before them has built: field sales organizations, customer success infrastructure, compliance certifications, vertical domain expertise, and the organizational capacity to manage thousands of enterprise relationships simultaneously.

OpenAI has embedded Forward Deployed Engineers within customer organizations. Frontier’s enterprise customers require SOC 2 Type II, ISO 27001, and a suite of related certifications. The EU AI Act begins enforcement in August 2026, introducing compliance requirements that did not exist when these companies were founded. Enterprise sales cycles sometimes stretch twelve months or longer for major deployments. These demand specialized teams that do not appear on a model company’s organizational chart.

The $30 billion Anthropic just raised is not exclusively for training runs. A meaningful portion of this capital will fund the construction of an enterprise go-to-market apparatus, including a sales force, compliance infrastructure, customer success organization, and vertical expertise. These are structural costs that permanently alter the business's margin profile. A model company has research costs and compute costs. A platform company has all of these, plus go-to-market costs that scale with customer count rather than compute capacity.

This creates a tension that the labs’ financial disclosures will eventually make visible. The transition from model economics to platform economics requires near-term margin compression to build the switching costs and network effects that expand margins over time. The trajectory of that compression and subsequent expansion will tell investors more about the durability of these businesses than any benchmark or revenue growth rate.

Meanwhile, the labs face a clock that the incumbents do not. Model advantages erode quarterly as open-source narrows the gap. If the labs do not establish orchestration lock-in before model commoditization is functionally complete, they risk becoming very expensive API utilities competing on price.

$380 billion does not price that outcome.

What this means for the public markets

When the prospectuses for OpenAI and Anthropic arrive, they will present revenue growth, gross margins, and customer counts in the language familiar to technology investors. That language will be necessary but insufficient.

If the analysis in this piece is correct, if these companies are transitioning from model businesses to platform businesses, then the central valuation question is not the rate of growth but the nature of the growth. Revenue from model API consumption and revenue from platform orchestration may appear identical in a financial statement. They are not identical in their implications for margin trajectory, competitive durability, or terminal value.

The companies that complete this transition will justify platform multiples. Those that do not will eventually be priced as API providers in a commoditizing market, regardless of current growth.

Distinguishing between the two before the market requires analytical frameworks that public filings alone cannot provide. The tools exist. The question is who applies them and when.

The single points of failure

Even if the orchestration thesis is correct and the labs successfully transition from model companies to platform companies, there are structural vulnerabilities that could undermine the entire strategy. In our analytical framework, we call these single points of failure (“SPOF”): risks that are not merely headwinds but existential if they materialize.

In this case, there are two potential SPOFs:

First, the open-source “compression”. Enterprises overwhelmingly prefer closed-source frontier models today. Research from UC Berkeley’s MAP study, the most rigorous field study of AI agent deployment to date, found that 85% of production agent systems run on proprietary models from Anthropic and OpenAI. Open-source adoption is limited to edge cases, such as high-volume workloads where inference costs are prohibitive, or to regulated environments that prohibit sending data to external providers. Enterprise teams default to the best-performing closed-source model available, and runtime costs are negligible compared to the human experts the agents augment.

This is encouraging for the labs. But it is a snapshot, not a guarantee. The preference for closed-source reflects a narrowing performance gap. DeepSeek’s V4 is expected to launch at any point now. MiniMax competes at the frontier from Shanghai. Alibaba just introduced the first open-weight Qwen3.5 model release. Open-source frameworks iterate without the constraints of enterprise SLAs or backward compatibility. If the performance gap closes sufficiently - and the trajectory suggests it will - the 85% preference could erode rapidly, because the underlying driver is pragmatic performance selection, not structural loyalty. Enterprises test the top models and pick the best one. If an open-source model becomes the best, they will pick it instead.

Then there is the compute trap. This is the risk that Dario Amodei himself articulated with remarkable candor, just last week, on the Dwarkesh Podcast. Asked why Anthropic does not spend more aggressively on compute given its belief that a “country of geniuses in a data center“ is imminent, Amodei’s answer was striking in its honesty about the financial fragility of the model: “If my revenue is not $1 trillion, if it’s even $800 billion, there’s no force on earth, there’s no hedge on earth that could stop me from going bankrupt if I buy that much compute.”

Pause on that. The CEO of a company valued at $380 billion is publicly stating that a miscalculation of even one year in the timing of revenue growth could be “ruinous.“ Data centers must be committed one to two years before they deliver compute. Revenue is growing tenfold annually. But if it grows fivefold instead, or if the tenfold growth arrives twelve months later than projected, the capital commitments become unserviceable. Amodei described the challenge as navigating a “cone of uncertainty“ where the technology trajectory is clear, but the revenue trajectory is not.

This is an unprecedented situation in enterprise technology. No company in the history of the software industry has operated at this level of capital intensity with this degree of revenue uncertainty over this compressed a timeline. Anthropic’s annual burn rate is approaching $8 billion. The $30 billion in fresh capital provides runway. But the runway at these burn rates is measured in years, not decades. And the compute commitments required to maintain frontier model performance only increase.

The tension is structural. To win the orchestration layer, the labs need frontier-quality models. You cannot orchestrate enterprise workflows with a mediocre model. To maintain frontier models, they need massive and growing compute investments. To fund those investments, they need the revenue growth to materialize on schedule. If the orchestration transition takes longer than the compute commitments allow, if enterprise adoption moves at enterprise speed rather than startup speed, the financial model fractures.

This is not a theoretical risk. It is the risk that Amodei identified publicly at the very moment his company reached a $380 billion valuation.

What this means

The SaaSpocalypse article examined the defenders of the enterprise technology stack and found a fraction of them more resilient than the market assumed. This piece has examined the insurgents and found them more strategically sophisticated than the “best model wins” narrative suggests. But also more financially exposed.

Together, the two analyses point to the same conclusion.

The labs are not hoping to win by building better models. They are, without doubt, building enterprise operating systems. The incumbents are not trying to survive AI. They are trying to become the orchestration layer before the labs accumulate enough context to displace them.

Both face clocks. The labs are racing against compute economics and model commoditization. The incumbents are racing against the labs’ speed of enterprise penetration.

In the enterprise, the question that will determine hundreds of billions in enterprise value is not who builds the best model, or even the best agent. It is who owns the accumulated understanding of how enterprises operate. It comes down to understanding which exceptions matter, which approvals are genuine gates, and which workflows can be safely automated.

Intelligence is commoditizing. Context compounds. Compute burns.

The race between all three will define the enterprise technology landscape for the next decade. The looming IPOs of OpenAI and Anthropic will be the market’s first real opportunity to price it.

This is the second in a pair of analyses on the structural shift in enterprise technology. The first, “The $285 Billion SaaSpocalypse Is the Wrong Panic,” examined the same shift from the incumbents’ side.